- About Ramapo

- Academics

- Admissions & Aid

- Student Life

- Athletics

- Alumni

- Arts & Community

- Quick Links

- Apply

- Visit

- Give

Investigative Genetic Genealogy Center (IGG)

February 5, 2024New lead in 1987 Wisconsin murder of Sandra Lison could produce third IGG exoneration

Image: Sandra Lison. Green Bay Press-Gazette. 6 Aug 1987.

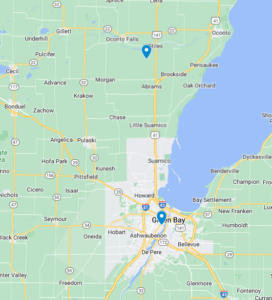

On the night of August 3, 1987, Sandra Lison—mother of two—disappeared from the Good Times Bar in Green Bay, Wisconsin, where she worked as a bartender. The next morning, Sandra’s body was found thirty miles north, in the rural Machickanee Forest. The evidence suggested that she had been beaten, strangled, and sexually assaulted.

Investigators initially focused on finding a man whom two customers at the bar saw speaking with Sandra in the early morning hours, making him the last person in the bar before closing. The man was never identified, and the case went cold. For eleven years.

Then, in 1998, a prisoner in the Oshkosh Correctional Institution began telling guards about the nightmares of his cellmate, David Bintz. The prisoner said that David would scream in his sleep about killing a woman. According to the prisoner, David yelled to “make sure she’s dead.” The prisoner told guards that he confronted his cellmate, and David admitted to helping his brother, Robert, kill Sandra after the two went to purchase beer from the bar and were annoyed at the high price.

Image: Robert Bintz. Green Bay Press-Gazette. July 27, 2000

Reviewing their notes, investigators remembered that they had spoken to David Bintz early in the investigation, and he had told them about driving to the bar to buy beer with Robert and a friend.

At some point in the investigation, a witness claimed that David Bintz had called in a bomb threat to the Good Times Bar on the night of Sandra’s disappearance.

Based on this evidence, in 2000, David and Robert Bintz were both tried for and found guilty of the murder of Sandra Lison. Robert took the stand in his own defense and denied committing the crime.

No physical evidence tied him or his brother to the crime. Indeed, DNA extracted from semen and blood found on Sandra’s remains excluded both David and Robert.

The man seen speaking to Sandra at closing time was never identified.

The source of the DNA from the blood and semen remained a mystery.

The two brothers’ appeals failed, and they remain locked in Wisconsin prisons. But based on the physical evidence pointing to another man, the Great North Innocence Project took on Robert’s case and began searching for the true perpetrator.

Around that same time, investigative genetic genealogy began making headlines. Along with the hundreds of perpetrators and unidentified remains discovered with the help of IGG, the method had been used to help exonerate two individuals.

In the summer of 2023, the Great North Innocence Project turned to the Ramapo College IGG Center to help identify the source of the rogue DNA. Another IGG organization had worked the case diligently in the preceding two years but had been unable to narrow on a candidate.

Over the course of three days, Ramapo IGG Center staff and students in the inaugural Ramapo IGG Bootcamp worked on the case in the secure IGG Lab housed in Ramapo College’s Learning Commons.

At the end of those three days, the Ramapo IGG Center team produced a lead: genetic genealogical analysis indicated that the source of the DNA was likely one of three brothers who were living in the Green Bay area at the time.

Map shows the location of the Good Times Tavern at 1332 S. Broadway on Aug. 3, 1987 and the Machickanee Forest, where Sandra’s body was located.

One brother stood out. Just prior to the attack on Sandra at the Good Times Bar, he had been released from a long prison sentence for crimes in 1981 where he, on two separate occasions, broke into the home of the same woman, where he blindfolded and raped her.

That same brother was later charged with calling in a bomb threat to a courthouse.

Based on this tentative identification, the Great North Innocence Project secured the cooperation of the district attorney to conduct additional DNA testing and comparisons. As IGG is only a lead, that lead must be confirmed with a direct DNA comparison.

That effort is ongoing.

The Ramapo College IGG Center is proud to have provided a lead in this case, which, if successfully confirmed, may lead to only the third time that IGG has been used to exonerate a wrongfully convicted man. This case helps fulfill one of our missions at the Ramapo IGG Center which is to expand the use of IGG in securing justice for the wrongfully convicted. Our Director, Prof. David Gurney, is especially pleased as the Great North Innocence Project (then the Minnesota Innocence Project) is where he first volunteered on a wrongful conviction case in 2012.

Our team approach was pivotal in this case. With a team of eight individuals working through the genetic and genealogical clues together, in person, we were able to make connections that a practitioner working alone could not have made in such a short time.

The case could not have produced a lead so quickly without the work or the students in our weeklong, intensive IGG Bootcamp. Those students, selected as individuals with the knowledge and experience—and ethical aptitude—to hit the ground running in an IGG case, showed their dedication to justice throughout their work on the case.

At this year’s Ramapo Investigative Genetic Genealogy (RIGG) conference, Jim Mayer of the Great North Innocence Project will serve as the keynote speaker, where he will discuss this case and other innocence work. Please join us. More information at registration here: https://www.ramapo.edu/igg/conference/

If you would like to learn more about our educational offerings—including the Ramapo IGG Bootcamp—please visit our website or contact our Director, Prof. David Gurney, dgurney@ramapo.edu, or our Assistant Director, Cairenn Binder, cbinder@ramapo.edu.

Categories: exonerations

January 22, 2024Words, Words, Words: Ancestry’s new Terms and Conditions remain vague for IGG

by David Gurney, JD/PhD – Director, Ramapo College IGG Center

New Boss, (Mostly) Same as the Old Boss

On January 17, 2024, Ancestry updated its Terms and Conditions (TaC) and Privacy Statement (PS). Some IGG practitioners are anxious over one new provision, which reads: “In exchange for Access to the Services, you agree: . . . Not to use the Services in connection with any judicial proceeding.”

If this provision includes IGG, then it is certainly cause for concern.

Ancestry’s services sweep wide.

They include not only tree building but access to public records held in Ancestry’s databases, which encompass sites like Newspapers.com, Find a Grave, and other essential repositories of public records that Ancestry owns.

If Ancestry truly banned IGG practitioners from accessing these services—and if IGG practitioners took Ancestry’s suggestion that “[if] you do not agree to these Terms, you should not use our Services”¹—IGG would become much more difficult, leaving violent criminals on the streets and families of victims and missing relatives without closure.

This post is meant to reassure the IGG community that, at least for now, Ancestry has decided to remain vague rather than address the issue of IGG head-on, and the new terms change little for IGG (though how Ancestry interprets its own terms is, as always, a black box), except perhaps for IGG practitioners who work on Maryland cases.

The clearest threat in the new language is to forensic genealogists who practice in heir searches and oil and mineral rights.

“It Depends on What the Meaning of the word ‘is’ is”

Before I explain why IGG can almost never be considered part of a judicial proceeding, I must address a change in Ancestry’s language w/r/t judicial proceedings.

In both previous and current versions of the TaC, Ancestry forbids the use of any “information obtained from the DNA Services . . . in any judicial proceeding[.]”² The new terms—in addition to applying the ban to all of Ancestry’s services, not just its DNA services—use a different phrase: not “in any judicial proceeding” but “in connection with any judicial proceeding.”

The question is whether the latter phrase is broader than the former. Looking at the phrase’s ordinary meaning shows that it is not.

But first, advocatus diaboli.

You might argue that the phrase “in connection with” sweeps as broadly as Ancestry’s services. Think of an IGG case involving the tentative identification of a violent criminal, the goal of the investigating agency is to bring a criminal case against the perpetrator in a judicial proceeding. Even though IGG occurs before any judicial proceeding begins, isn’t IGG being used “in connection with” a future judicial proceeding here? And, therefore, don’t Ancestry’s new TaC forbid the use of its services for IGG?

Courts looking to interpret a phrase will first look to see if the document containing the phrase provides a definition (Ancestry’s TaC do not), and barring that, will turn to the humble dictionary.

Here, various dictionaries provide synonyms such as “about”, “concerning”, “regarding”, and so on, and Webster’s defines the phrase as “in relation to (something).”

Do these interpretations vindicate the view that Ancestry’s new TaC forbid the use of its services for IGG?

Well, no, at least not in the ordinary sense of the phrase “in connection with”. The dictionary is unhelpful here, and when that is the case, courts turn to something even more powerful: the ordinary use of a phrase. When we, too, make that turn, the meaning of “in connection with” in this context becomes clear.

Consider an analogy:

Imagine that a large computer company offers its services to the public in general. The company is concerned about the appearance of impropriety if its services are used in a public-school graduation ceremony, so it includes a provision that reads: “Our services may not be used in connection with a public-school graduation ceremony.”

Now, imagine that a public high school adopts the computer company’s services for use in its classrooms and administrative offices. But the school is careful not to use the services during its graduation ceremonies so as not to fall afoul of the terms of service.

Nevertheless, at a school-board meeting, a parent takes the microphone and says that the school must stop using the computer company’s services in any way. The parent argues that, after all, one of the primary goals of public school activities, both in the classroom and in the administrative offices, is to move students toward graduation. Indeed, a graduation ceremony is inevitable. Thus, the parent argues, any use of the computer company’s services by the school is “in connection with a public-school graduation ceremony.”

This, I hope it is clear, is an unreasonable understanding of the phrase “in connection with.” It includes any activities that might lead to a particular outcome—in this case, a graduation ceremony. Heck, a student’s use of the computer company’s services for homework would be banned under this interpretation.

The parent’s interpretation is not just unreasonable when considering the ordinary use of the phrase. It is further unreasonable due to another rule of judicial interpretation: if the drafter of a document intended a provision to have a particularly broad impact, they would have made a clear statement to that effect. If the computer company’s intention was to forbid the use of its services for any activities with any relation to a public school graduation ceremony, they would have done so plainly. They would not have hidden that intention in vague language.

Rather, the computer company’s intention—based on the most reasonable reading of its language—was to ban the use of its services as part of a public school graduation ceremony, which includes the ceremony itself and likely any activities directly related to it, such as promotional materials.

Ditto with Ancestry’s new TaC.

The use of “in connection with” does not implicate all activities that precede a judicial proceeding that may or may not come to be. The most reasonable reading of the phrase, instead, includes a judicial proceeding itself and activities directly related to it, which I will describe in more detail below.

What is a “Judicial Proceeding” Anyway?

So, the question becomes: is IGG part of a judicial proceeding?

Again, the answer is no, in almost every context.

Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute defines a judicial proceeding as “any proceeding over which a judge presides [] [which] may include quasi-judicial proceedings [where any officer of the court exercises judicial functions that make legal determinations].”

The overwhelming majority of IGG work will never take place within a context where a judge or other official presides and where legal determinations are being made.

IGG nearly always takes place before any judicial proceeding, as it is inherently investigative in nature. IGG practitioners are hired by (or work for) investigating agencies to help identify leads. Those leads may produce evidence that is then used in a criminal case or by a medical examiner.

There are three contexts where IGG work might be considered as part of a judicial proceeding, but all are murky.

The first context is an IGG practitioner working on a Maryland case. Maryland’s law that regulates IGG requires a judge to sign off before IGG begins, and there is judicial oversight built into the entire process. There, IGG could be seen as occurring as part of a “judicial proceeding,” and thus, the use of Ancestry’s services would be forbidden. But even there, it’s not entirely clear that the IGG work itself occurs as part of a judicial proceeding. The act of getting the warrant signed by the judge is undoubtedly a judicial proceeding since the judge is overseeing a particular event and applying the law. But unless IGG work is used in that warrant hearing–which it wouldn’t be since it wouldn’t have begun yet–the judicial proceeding is limited to the specific event of signing the warrant. At the same time, the IGG work might seem to be at least part of a judicial proceeding here, as it is allowed to go forward only because a judge has signed off on it.

The second context is again within the confines of Maryland’s law. That law requires judicial notification if a prosecutor wishes to obtain a covert sample from a reference tester. Perhaps notifying the judge constitutes a judicial proceeding. But two questions arise: does that proceeding include use of Ancestry’s services? And, if so, is the one using those services bound by Ancestry’s TaC? These questions are not easy to answer. In arriving at the identity of the reference tester, Ancestry’s services may have been used. Thus, providing the name of the reference tester to the court is arguably a use of Ancestry’s services as part of a judicial proceeding. Yet, the prosecutor is not bound by Ancestry’s TaC (unless they conducted the IGG themselves), and it is the prosecutor who is using Ancestry’s services here as part of a judicial proceeding. It is not clear that the IGG practitioner’s actions in generating the identity of the reference tester constitute the same. But again, if you take the view that all IGG work conducted in a Maryland case is part of a judicial proceeding since a judge signed off on it, then the interpretation changes.

The third context is where an IGG practitioner testifies about their findings either in pre-trial or at the trial itself. This context is particularly murky since the IGG work itself—and the use of Ancestry’s services—will have occurred before the judicial proceeding; indeed, before it was even certain that there would be a judicial proceeding. Assuming the case is not in Maryland, at no time did the IGG practitioner use Ancestry’s services as part of a judicial proceeding. By the time of the judicial proceeding, those services have already been used. They helped lead up to the judicial proceeding but are not a part of it. Think again of the public high school graduation ceremony.

Words, Words, Words

Ancestry has chosen to keep its TaC vague as they apply to IGG practitioners’ use of Ancestry’s services.

They did not have to.

Ancestry’s previous and current Privacy Statement contains the following sentence: “We do not allow law enforcement to use the Services to investigate crimes or to identify human remains.” Some have taken this statement to forbid the use of Ancestry’s services for IGG. But the statement must be taken in context. The Privacy Statement document is about how Ancestry will act, it is not about how users of Ancestry should act. The statement about IGG occurs as part of a description of how Ancestry will share information. Before the statement, Ancestry notes that it does not voluntarily provide data to law enforcement. They are talking here about law enforcement who comes to Ancestry and asks them to turn over information about individuals. We all know that Ancestry will not comply with these requests without a warrant. This context is important.

Ancestry could have chosen to import that phrase—“We do not allow law enforcement to use the Services to investigate crimes or to identify human remains”—into its new TaC for users of Ancestry’s services.

Instead, Ancestry chose to remain vague.

Why, is anyone’s guess.

Forensic Genealogy

There is some genealogical work that clearly takes place in the context of a judicial proceeding.

Forensic genealogists who work on locating heirs to estates, real estate, and mineral and oil rights cases are frequently hired as part of an ongoing judicial proceeding—sometimes even by the court itself.

I would argue that it is these forensic genealogists who should be most concerned with Ancestry’s new TaC.

What Happens Next for IGG

Is unclear.

I believe my interpretation here is correct based on the language that Ancestry has used. But again, what Ancestry intends in its soul is inaccessible.

I hope that business will continue as usual and that Ancestry will not clarify its terms to explicitly forbid IGG—or use its existing terms to ban users.

Either step would be, in my view, an act of cruelty.

IGG practitioners use Ancestry services primarily for access to public records. Many—but not all—of these records can be accessed elsewhere, but doing so requires more work, and more time. Time that cold cases, with all their attendant suffering, will remain unresolved.

Ancestry cannot stop IGG, but they can, if they choose, slow it down.

If that is Ancestry’s goal, only time will tell.

__

¹The use of “should” here is unusual. Typically, when a company wants to block certain activities on its sites, it will do so using terms like “must” and “shall.” “Should” is a vague term. As this blog post will make clear, vagueness is Ancestry’s hallmark, so it is no surprise that they retain it here.

²This provision caused little concern for IGG practitioners since they would be unlikely to be users of Ancestry’s DNA services themselves and so would not be bound by the provision.

Categories: terms of service

January 22, 2024The emotional impact of working in Investigative Genetic Genealogy

By Cairenn Binder — January 19, 2024

My friend Jarrett Ross recently posted a video on his YouTube channel Geneavlogger titled, “Why I Quit Investigative Genetic Genealogy”, which describes his journey working as an investigative genetic genealogist and lists his reasons for leaving the field. I was surprised to learn that anyone would voluntarily leave a position in IGG because paid work for practitioners is so sought after. When I viewed the video, however, I could see why someone would make the decision to move on – and recognized some commonalities that I believe are experienced by many IGG practitioners. Jarrett describes the seepage of his IGG career into his personal life – causing fatigue, exhaustion and preventing him from pursuing other passions.

Jarrett also describes how exciting it was to narrow down leads and help to solve cases of violent crime and unidentified human remains. The thrill of the chase is what draws so many to the field, and the satisfaction of helping bring justice to victims of violent crime is the icing on the cake. With that said, there are some enormous drawbacks to working in IGG, and it is worth examining them before making a decision to jump into this career.

The stories are harrowing

IGG practitioners are tasked with generating investigative leads in some of the most grisly violent crimes imaginable. While our “need to know” is the bare minimum, we are often subject to learning the details of the crimes we are researching, and they can be haunting. It is common for IGG practitioners to express affinity with victims and their families, and traumatic stress, and fear for their personal safety and security – all related to working violent crime cases.

Working in nursing prior to my career in IGG, I am accustomed to hearing and seeing unpleasant things. I have experienced a patient die in one room, and two minutes later put on a smile for a person giving birth to new life in the next room. As a healthcare professional, I learned to steel myself from becoming too invested in the lives of my patients, instead remaining task-oriented and compartmentalizing my feelings.

In IGG, I do the same. Typically, I do not read about any details that I don’t need to know for my casework. I celebrate the success of generating a lead with my team(s), and take a moment to internally acknowledge the victim or decedent when the lead is confirmed. I try not to get too invested.

Even so, occasionally the details of a case will hit close to home, which can be extremely distressing. The case of Wendy Stephens was particularly difficult for me – killed at just 14 years old, she’d barely had the chance to find her way in the world before her life was taken. My own daughter was 14 when this case was solved, and it was impossible to keep my emotions at bay in spite of my efforts.

You will feel insecure

IGG is a rapidly evolving field. Keeping up with active cases playing out in court, ever-changing database and resource terms of services, and tracking newly introduced legislation could be a full-time job. My Director David Gurney often states that we are playing “Whack-a-Mole” contending with legislation meant to regulate IGG while simultaneously misunderstanding how IGG works.

When I worked in healthcare, job security in my industry was never a worry. With a near-constant shortage of nurses, I was not concerned that new legislation banning my industry altogether could impact my livelihood.

In IGG, it is true that on any given day, new legislation or a database change could erase the industry entirely. This may be a contributing factor to the discord that seems ever-present in IGG, along with the scarcity of IGG-related jobs to begin with. Living in this reality means contending with some degree of fear and uncertainty – all the time.

The work will bleed into your personal life

Once again, I have to look back on my career in healthcare as it contrasts so greatly with my current role. Rarely, if ever, did I feel compelled to check my work email account on a day off when I worked as a nurse. Never did I start working until I had actually arrived at work.

Today, however, I opened my eyes at 5:30am and immediately logged on to find out if new matches had populated in a case the IGG Center is working on. It is a common occurrence for me to check my work email and even perform work tasks in the evening or while on vacation. The ability to disconnect and maintain a healthy work-life balance feels significantly more challenging in IGG than it did in my previous career.

IGG practitioners are widely discussed and criticized

The practice of IGG has been debated in the media, in blogs, and in social media since its inception. Crusaders with privacy concerns arguing passionately for tighter legislation face off against investigators and IGG practitioners advocating for the continued practice of IGG. For people working in the field, it is impossible to escape the deluge of vitriol aimed at IGG practitioners.

I experienced this myself in the summer of 2023 when an article was published naming me as an IGG practitioner who had viewed opted out DNA matches in IGG cases. This was the result of a security flaw in programming of some tools which caused opted out matches to appear in outputs, and many (if not most) practitioners were aware of this “loophole”.

IGG practitioners who were named in the article were, for months, on the receiving end of hateful remarks that went above and beyond criticisms of our practice. I was shocked and saddened to be thrown under the proverbial bus by friends, colleagues and strangers alike who seemed glad of a scapegoat during that time period. It was impossible to escape the comments sections of various social media posts where people openly cheered my and my colleagues’ degradation – well-meaning people sent them to my messages asking, “have you seen what ___ said about you today?”

For months my mental health was impacted by the fallout, but living in the microcosm that is the online “IGG debate” community is not advisable. Thankfully, I was able to get myself outside, reconnect with my friends and hobbies, and realize that the world is full of many people – and most of them do not write bad things about me online.

Discussion and debate are vital to progress, which is why we welcome criticisms of IGG at RCNJ’s annual IGG conference, RIGG. IGG practitioners should be aware, however, that some critics are wont to spout hyperbole and personal attacks in their campaigns against IGG practitioners.

How to cope

While the field is incredibly difficult to work in, IGG certainly has its rewards. It is a career that can be worked, in many cases, entirely remotely – offering desirable flexibility and comfort. It is one of the few careers in which civilian true-crime enthusiasts can impact the path to justice for victims. It is a fun job where friendship, teamwork and collaboration are critical to success. Finally, it is a career in which a single person can make a lasting impact for good in the world. I count myself lucky to be here, in spite of the challenges.

While I don’t always take my own advice (working on it!), I am happy to dole it out. Here are my tips for maintaining balance and a positive mindset while working in IGG:

- Utilize mental health resources. We are fortunate to live in a time where mental health is becoming more of a priority, and utilizing mental health care has become less stigmatized. There are many resources available to members of the general public at no cost, including crisis hotlines and online wellness guides. This guide from the NIH has a listing of some available resources.

- Draw healthy boundaries. A former student in the Ramapo IGG certificate program once shared her experience as an emergency services operator, during which she would receive calls from people in distress during the most critical periods of their lives. She described the process of separating her work and home life, essentially “hanging up” her job at the end of the day and not taking her work home with her. The same can be applied to IGG – it is difficult to compartmentalize and separate ourselves from our casework, but it is necessary to avoid burnout and traumatic stress. Setting working hours and avoiding thoughts of cases and casework while not working is one way to draw a healthy boundary and protect your mental health.

- Avoid online discussions. I have learned the hard way not to argue with people online. It never resolves the situation, and in fact only increases post engagement for the people starting the arguments. When it comes to spirited debate that devolves into personal attacks, remember that hurt people hurt people and the attack is probably not really about you. Debate is necessary, but fighting on social media will not result in any big wins for IGG and only serves to make everyone look bad.

- Touch Grass. When you are nose-deep in casework, engrossed in social media, and working all hours of the day to promote your IGG career, it is easy to lose sight of the wider world. When you’re feeling overwhelmed, overworked, or overly zealous, it’s time to disconnect. Go for a walk without your phone (I personally enjoy a nice graveyard walk) and remember that there is a world outside of IGG.

Categories: practitioner tips

Copyright ©2025 Ramapo College Of New Jersey. Statements And Policies. Contact Webmaster.

Follow Ramapo