- About Ramapo

- Academics

- Admissions & Aid

- Student Life

- Athletics

- Alumni

- Arts & Community

- Quick Links

- Apply

- Visit

- Give

Resources

Book Reviews

Richard Overy, Interrogations: The Nazi Elite in Allied Hands (New York: Viking Penguin, 2001)

This new work by one of Britain’s most prolific historians of the Second World War, throws added light on the motivations and behavior of Hitler’s leading henchmen with regard to a number key issues in the Third Reich, including the war against the Jews. Interspersing cogent analysis with quotes from their pretrial interrogations, a web of complicity is drawn, leaving no doubt about how and who implemented the Holocaust.

Not surprisingly, higher-ups like the ideologue Alfred Rosenberg or the Governor of rump Poland Hans Frank vehemently denied any part in the genocide of the Jews. They admitted their anti-Semitism, but they distanced themselves from any involvement in murder. Even SS-General Erich von dem Bach-Zalewski, who was in charge of putting down the Warsaw uprising, tried to convince his interrogators that he had attempted to warn the Jews of Ukraine of the murderous intent of his superiors. According to Overy, in appearing as a witness for the prosecution, Bach-Zalewski demonstrated that he was actually in part successful.

Less able to deny their participation, lower level perpetrators provided the essential details of the Holocaust that gave a hollow ring to the denials of their superiors. The accounts of Adolf Eichmann’s notorious aide, Dieter Wisliceny, and Otto Ohlendorf, commander of Einsatzgruppe D were particularly damning. As Overy notes, they probably revealed their roles in the Nazis’ murderous enterprise in order not to let their superiors off the hook.

This was especially evident, for example in the testimony of Wisliceny regarding the deportations of Slovak Jewry:

Eichmann then stated that a visit by a Slovak commission in the area of Lublin would be impossible. When I asked why, he said, after much delay and a great deal of discussion, that there was a order of Himmler according to which all Jews were to be exterminated… He took the order from his safe. He then searched and took out this folder. It was a thick file. He then searched and took out this order. It was directed to the Chief of the Security Police and the Security Service [Heydrich]. (p.359)

Finally, Overy in analyzing these bleak testimonies comes up with some significant findings about the genesis of mass murder. Anti-Semitism, he acknowledges, was crucial to the mindset of those carrying out racial policy in its most extreme forms. Moreover, according to Overy, in reading through the interrogations it becomes apparent how readily the Third Reich’s culture of oppression and obedience led to the Final Solution. Perhaps not surprisingly, he concludes his discussion of this transition somewhat clinically:

This deadly cocktail of uncritical prejudice, moral abdication and reflexive violence produced a casual indifference to suffering and an easy familiarity with pervasive morbidity of the camps.” (p. 198).

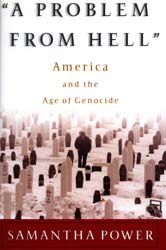

Samantha Power, “A Problem from Hell:” America and the Age of Genocide (New York: Basic Books, 2002)

In her important new study on U.S. policy towards genocide, Samantha Power argues successfully that government leaders have consistently thwarted the efforts of activists and a few brave officials in moving our government to prevent it. Through dogged research and interviews with key players, she shows how this was as much the case in the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust as it was more recently in Cambodia, Iraq, Bosnia, and Rwanda.

In her important new study on U.S. policy towards genocide, Samantha Power argues successfully that government leaders have consistently thwarted the efforts of activists and a few brave officials in moving our government to prevent it. Through dogged research and interviews with key players, she shows how this was as much the case in the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust as it was more recently in Cambodia, Iraq, Bosnia, and Rwanda.

However, as Power demonstrates, not only public officials have been responsible for the lack of action. Public apathy has fed official inertial, as well. As Power writes: “Because so little noise has been made about genocide, U.S. decision makers have opposed U.S. intervention, telling themselves that they were doing all they could do – and, most importantly, all they should – in light of competing American interests and a highly circumscribed understanding of what was domestically ‘possible’ for the United States to do (p. 509).” Still, as Power sees it, this is where political leadership should have broken the ring of inertia. Regrettably, elected officials, from the Oval Office on down, rather than mobilizing public opinion in favor of action have consistently concentrated their efforts on trying to restrain it.

A good deal of Power’s study is devoted to the groundbreaking work done by the Polish-Jewish legal scholar and activist, Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide. Originally outraged by the lack of international action in the killings and “ethnic cleansing” of the Armenian Massacres (as this undeniable act of genocide was then called), he came to believe that only by making such crimes illegal under international law was there a chance that they could be prevented from occurring in the future. Himself a refugee from the Holocaust, with 49 members of his family murdered, Lemkin intensified his efforts into a crusade. He quickly determined that his quest required a new word to describe what had happened to the Armenians and Jews.

According to Power, “His word would do it all. It would be the rare term that carried in it society’s revulsion and indignation. It would be what he called an index of civilization (p. 42).” The result combined the Greek derivative, geno, meaning “race” or “tribe” with the Latin derivative cide, meaning killing. She cites his 1944 book, Axis Rule in Europe, to make it clear that Lemkin was not thinking solely in terms of the Shoah. He meant to devise a term that would be generally applicable to describe “a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves (p. 43).”

In the end, Lemkin’s crusade did at least achieve the partial success of the passage by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948 of the Genocide Convention. Nevertheless, as Power c1early and repeatedly shows , Lemkin could not know that “the most difficult strugg1es lay ahead. Nearly four decades would pass before the United States would ratify the treaty, and fifty years would elapse before the international community would convict anyone for genocide. (p. 60).

Copyright ©2025 Ramapo College Of New Jersey. Statements And Policies. Contact Webmaster.

Follow Us!