- About Ramapo

- Academics

- Admissions & Aid

- Student Life

- Athletics

- Alumni

- Arts & Community

- Quick Links

- Apply

- Visit

- Give

Where is the Justice? A Fight for Same-Sex Marriage Through a Comparison of Interracial Marriage

(PDF) (DOC) (JPG)June 15, 2017

KRISTI INTORRE[1]

A young version of myself is sitting on the couch while my mother paints my toenails. “Uncle Tommy is not married,” I said. “So why does he always go on vacation with another boy?” I asked my mother. Earlier I had learned that my uncle was unable to attend my fifth birthday party later in the week due to his travel plans. “Uncle Tommy loves differently than your daddy and me,” my mother replied. “So Uncle Tommy loves the boy he goes on vacation with?” I inquired. “Would you love your uncle any less now?” She did not look at me as she asked. “Why would I love him any less?” I replied with confusion. My mother did not answer. This brief conversation has lingered on and has influenced the way I perceive love and marriage. As I grew older, I began to comprehend the harsh reality that society did not accept same-sex relationships. The conversation I had with my mother has been a constant reminder that regardless of sexual orientation, every single human being has the right to love whomever they desire and should have the right to marry the person they love.

This essay explores the question of same-sex marriage from the perspective of individual entitlement to the basic human right to marriage. The fundamental right to marriage was recognized by the USSC in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) to include a right of same-sex couples to marry in all states of the US. The Obergefell Court found no “lawful basis for a state to refuse to recognize a lawful same-sex marriage performed in another state on the ground of its same-sex character.” Even though the Supreme Court recognized same-sex marriage and provided marriage equality, social acceptance of same-sex relationship is not universal, and it varies from state to state. This is comparable to the anti-miscegenation laws, which denied interracial couples to marry until the United States Supreme Court declared such laws unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia (1967). The laws against interracial marriage and civil rights history afford valuable lessons for the debate about marriage equality. Through an analysis of case law, my paper explores the legal discourse on recognition of the right to marriage to all individuals in all states of the United States, without discrimination based on identity of a person.

History repeats itself: interracial marriage and same-sex marriage

The moral disagreement over same-sex marriage amongst states parallels the debate over interracial marriage- with some states accepting and some states forbidding the marriage between whites and blacks until 1967 (Koppelman, 2005). In a landmark ruling, United States Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia deemed that laws banning marriage on the basis of race are unconstitutional. The Supreme Court’s decision in Loving heralded a change in the social acceptance of interracial marriage and racial tolerance in our society.

Anti-miscegenation laws are deeply rooted in American history, dating back to the 1630s and 1640s when interracial sexual activity was seen as contrary to the “natural” social order and therefore prohibited. Those who engaged in interracial sex were publicly humiliated and whipped. Society acknowledged only same-race intimacy and marriage, specifically restricting relationships between whites and non-whites. This long-standing racial intolerance against the nonwhites is thus ingrained in American culture and helps explain why laws barring interracial marriage were active until recent history (Moran, 2001).

In the years preceding the Civil War, anti-miscegenation laws existed to define racial identity and enforce racial inequality. The laws’ purpose was to establish racial boundaries, contain racial ambiguity, and preserve sexual decency. After the Civil War, with the abolishment of slavery, the regulation of sex and marriage among races played an important role in defining the color line between white and blacks (Moran, 2001). Anti-miscegenation laws acted as a “central sanction in the system of white supremacy” (Koppelman, 2005, p. 2150). It was enforced “to block black(s), (from) access (to) privileges of associating with whites” (Moran, 2001). White supremacists spent an enormous amount of time and energy to prevent interracial marriages from occurring as a measure to preserve social order and to keep the color line firmly in place. Legislators enacted strict regulations to prohibit interracial sexual acts and more importantly, marriages (Koppelman, 2005). They believed that allowing marriages between blacks and whites, would threaten the presumption that blacks were “subhuman slaves incapable of exercising authority, demonstrating moral responsibility and capitalizing on economic opportunity” (Moran, 2001, p. 19). They feared that interracial marriages between whites and blacks would undermine white privileges, such as property protections that inheritance laws offered (Moran, 2001).

Even so, the regulation of interracial marriage was not uniform throughout the country. Before Loving, sixteen states had existing legislation that banned interracial marriage (The Official Site of the Tennessee Government). There was confusion across the nation on the validity of interracial marriages outside of the state that a couple was married in. Couples travelling or moving from states that allowed interracial marriage to states that prohibited such marriages potentially found themselves imprisoned or fined for violating a state law (Wallenstein, 1999).

Additionally, there is confusion concerning a state’s interest with regards to marriage, especially with regards to residency status of individuals. For instance, in North Carolina, where interracial marriage was prohibited, the difference in the Court’s ruling in two similar cases, ruled in the same year, State v. Kennedy (1877) and State v. Ross (1877) showed the legality of interracial marriages might be tied to gender and residency requirements. In State v. Kennedy (1877) a couple that resided in North Carolina temporarily went to South Carolina to get married, and returned to North Carolina right after their marriage. Even though they were legally married in South Carolina, North Carolina proved to have greater interest in their marriage since they were residents of the state. Thus, North Carolina’s court deemed their marriage illegal and punished them for fornication and adultery, finding that the couple purposefully attempted to evade the North Carolina law. This reasoning, however, was not applied in a later case the same year in State v. Ross (1877). In this case, the husband was a citizen of South Carolina prior to the marriage and the wife, a resident of North Carolina, who travelled to South Carolina to get married. After their marriage, the two remained in South Carolina for three months, before permanently relocating to North Carolina. In this case, the Court acquitted the couple owing to the brief domicile in South Carolina before returning to North Carolina, and recognized their marriage. The court also determined that since the wife acquires the domicile of her husband upon marriage, South Carolina has the greatest interest of their marriage in this case (Wallenstein, 1999).

The decisions in Kennedy and Ross allow for some interpretation that there was a possibility to have a valid interracial marriage in North Carolina, even though the state prohibited it. More importantly, it showed the challenges of legal marriages not being recognized outside of the states where the marriage took place and also, the complexity of how the greater interest of a state applied to marriages, based on residency. Unlike North Carolina, some states refused to accept interracial marriage under any circumstances, regardless of determining a domicile in state that recognized interracial marriage. For instance, Tennessee refused to recognize any interracial marriage regardless of the validity of the marriage in a couple’s state of origin (Wallenstein, 1999). Hence, for couples that ventured to other states to marry, it remained unclear if their marriage would be considered valid in their home state. Would their children, if any, be considered legitimate?

The inter state issues that were central to the non-acceptance of interracial marriage in the country are also seen in the debate over same-sex marriage. The belief that states have the right to govern their own residents and have a strong interest in the matters of marriage dominates the discussion of same-sex marriage. Unlike interracial marriages, it was not uncommon for same-sex couples to marry in a state that recognizes same-sex marriage and then return to their state of domicile. While same-sex couples could domicile, uncertainties about recognition of their married status remained. It impacted couples’ ability to reside, travel, work, etc. as their relationship was not protected in all states. As Ruskay-Kidd argues “the very nature of marital vows, ‘in sickness and health … as long as you both shall live’ transcends time and place; the power of these vows would evanesce if they concluded instead with the words …‘or until the both of you shall travel to another state” (Ruskay-Kidd, 1997). It is unjust that the status of marriage changed when same sex couples crossed state lines, as some states denied same-sex marriages validated in another state, until the Obergefell decision. Social acceptance of same-sex relationship, however, remains a challenge.

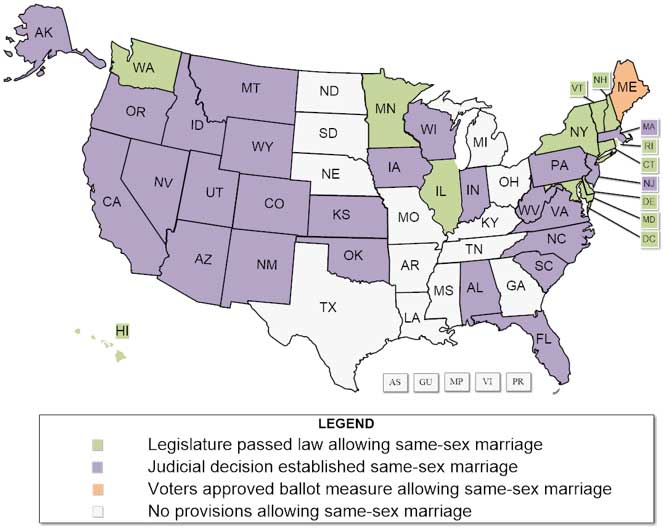

In the past interracial extraterrestrial marriages contrary to a state’s strong public policy or state law were almost never recognized, as seen in State v. Kennedy. Prior to Obergefell, thirteen states prohibited same-sex marriage, and there was no law to protect valid marriages from state to state (National Conference of State Legislature, 2015). For example, at one point in time:

Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, New Hampshire, Texas, Utah, and Virginia had statutes that explicitly prohibit[ed] same-sex marriages. Many states, including California, Colorado, Illinois, and Florida, had statutes that define[d] or referre[d] to marriage as the union of a man and a woman. In other states, such as Minnesota, Kentucky, and Washington, as well as the District of Columbia, challenge[d] statutes that [did] not specify the sexual make-up of marriage partners have been rejected by courts (Feldmeier, 1995).

There were no laws to protect interstate same-sex marriage, a dilemma that was similar to earlier interstate interracial marriage. While same-sex marriage debates are seen as a question of LGBT rights, the parallel with inter-racial marriages shows a pattern that is structured within the notion of state rights.

Image provided by:

Same-Sex Marriage Laws, National Conference of State Legislature, March 19, 2015, http://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/same-sex-marriage-laws.aspx.

Legal recognition of same-sex marriage

The legal recognition of same-sex marriage did not become a leading, national conversation until 1993 when same-sex marriage won its first partial victory in its fight for marriage equality in Hawaii in Baehr v. Lewin. This was the result of a challenge by three same-sex couples who were denied marriage licenses by the Director of the Department of Health because they did not meet the requirement of being opposite sexes. Although the trial court dismissed their challenge, they appealed to the Supreme Court of Hawaii seeking to have the same-sex exclusion for marriage deemed contrary to the Hawaiian State Constitution. The Court ruled that Hawaii’s constitution’s right to privacy did not include a fundamental right to same-sex marriage. However, the Court found sex-based classification for marriage unconstitutional and in violation of the equal protection clause of Article I, Section 5 of the Hawaii Constitution (Kersch, 1997). It was thereby remanded to the trial court to determine if the state could meet the standard of strict scrutiny by upholding the requirement of opposite-sex couples to obtain a marriage license as a compelling state interest (Kersch, 1997). This was indeed a major victory for same-sex marriage, as the Court established that sex based classification could not meet the standard of strict scrutiny.

While the judicial victory in Hawaii was short lived, as it was overridden by a statewide ballot reserving marriage to opposite-sex couples, it invigorated a conversation about sex-based classification in marriage laws. States questioned whether they would have to recognize same-sex marriage from Hawaii, or any other state. They examined the possibility of the Court’s determination in Baehr reaching a national level, leading to reexamination of the Full Faith and Credit Clause of the United States Constitution.

The Full Faith and Credit Act, primarily meant to facilitate debt collection for creditors, requires states to extend full faith and credit to out-of-state public acts, record and judicial proceedings (Kersch, 1997). States have construed the purpose of this clause to include legislation that allows them to exclude marriages based on prejudice, not fact and law. The norm prior to the debate on same-sex marriage was that of the place of celebration rule, or the Latin “lex loci celebration” to determine who is married (Ruskay-Kidd, 1997). The tradition of lex loci celebration allows married couples to travel freely without concern that their marriage may be affected in another state. In the case of same-sex marriage, lex loci celebration conflicted with state power, as traditionally states have had a “strong and legitimate sovereignty interest in governing the marital relationships of their domiciles” (Kersch, 1997). Thus, the language of this clause does not provide a legal standard to resolve the issue of comity in the context of same-sex marriage.

Additionally, under the norm of good faith, states could refuse to recognize a marriage if a couple went to another state to marry to avoid their own state’s marriage laws. Moreover, although intention of good faith is to recognize a marriage as the domicile state would, a valid marriage may not be recognized in another state if the recognition would be contrary to a strong public policy of that state (Feldmeier, 1995). Nevertheless, there is a strong argument for states to refer to the state where a marriage is celebrated to determine its validity:

Whether based on notions of comity, full faith and credit, or public policy, states have generally held to this principle and evaluated the validity of marriages using the law of the state or country where the ceremony took place. Most of these legal opinions have denied same-sex marriages based on relaxed interpretations of equal protection requirements or traditional definitions of marriage (Feldmeier, 1995, p. 121-122).

Prior to the Baehr decision, twenty-one [states] had no cross-recognition statutes, fourteen had enacted the common-law rule that a marriage valid where celebrated is valid in their state, and sixteen states had so-called evasion statutes under which their residents could not marry elsewhere in order to avoid the marriage laws of their state (Kersch, 1997).

In anticipation of the Baehr decision, some states amended their constitutions to ensure that permitting same-sex marriage would fall contrary to the state’s strong pubic policy (Kersch, 1997). This allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages, without violating the provisions set forth by the Full Faith and Credit Act. Further, there was no consistency amongst the states involving interstate marriage. One of the functions of the Full Faith and Credit Act is to bring uniformity in the laws, however the clause was seen as moot due to the power of states to refuse recognition of a marriage if it was contrary to their public policy. Essentially, this meant that there were no laws or securities to ensure the validity of marriage from state to state for non-traditional heterosexual couples, and this not only limited the rights of same-sex couples, but also added duress. It restricted same-sex couples’ ability to move throughout the country, amongst other restrictions.

Because marriage is a long term continuing relationship, couples should not have to re-determine the validity of marriage. In the past, in cases of interracial and consanguineous marriages, the courts have recognized marriages contrary to the strong public policy in instances of death and dissolution, especially with respect to issues of property and inheritance. Courts were willing to acknowledge these marriages because they were not enabling or allowing such marriage to continue, they were actually enforcing the end of the marriages (Koppleman, 2005). Further, the cases typically involved specific parties, with no threat to the society as a whole. These exceptions did not apply in the case of same-sex marriage, and hence, it became important to implement the Full Faith and Credit Act to engender legal and social acceptance of same-sex relationship in all the states (Kersch, 1997).

Additionally, it is important to note that the public policy exception applied to protect vulnerable parties in a relationship such as the young, the mentally incompetent, multiple wives or close family members. This should not extend to same sex couples (Russay-Kidd, 1997). The public policy exception is grounded in a need to protect vulnerable individual in cases where one partner in the relationship needs protection or is not competent to understand the implications of the arrangement; this does not apply to same sex couples. The insistence in the denial of same-sex marriage, therefore, was consistent with concerns about interracial sentiment “rooted solely in biases about the identities of the parties and the morality of their combination. The feelings evoked by the marriages of persons of different and ‘unnatural’ are echoed in the modern debate over same-sex marriages” (Russay-Kidd, 1997, p. 1442).

Further, the mere fact that some states did not have an interstate policy until Baehr came into discussion indicates that the policies targeting same-sex marriage were not deeply rooted in the state’s history and that they were only created to demote homosexuals based on personal beliefs and opinions.

The role of personal biases is evident in the enactment of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) of 1996. This Act was openly in objection to gay marriage, passed in Congress in response to the Hawaiian Supreme Court’s decision that prohibiting same-sex marriage violated the state’s constitution, thus preempting similar recognition in other states. DOMA was propelled by the anti-gay sentiment in the country because “most people do not approve of homosexual conduct…and they express their disapprobation through the law…it is…the only possible way to express this disapprobation” (Litigating the Defense of Marriage Act, 2004, p. 2684).

DOMA’s provisions suggest that it was indeed drafted to preempt the possibility of claims to recognition of same sex marriage in the near future, as Congress categorically excluded gay couples from the definition of marriage. Two sections of DOMA stand out. Section Two of DOMA determined that no State would be required to give any effect to any judicial proceeding or record in respect to a relationship between persons of the same-sex that is treated as a marriage under the laws of another State. Essentially, it empowered states to disregard same-sex marriage validated in another state, thus cancelling the operation of the Full Faith and Credit Clause. Moreover, DOMA also determined that marriage would be defined at a national level as a legal union between one man and one woman and that the word spouse referred only to a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or wife. As Russay-Kidd argues, DOMA undermined the traditional role of the States in defining marital status by creating an unprecedented federal definition of marriage (Russay-Kidd, 1997).

DOMA was not the only act by the government that restricted same-sex couples. It begins with the 1986 Supreme Court ruling in Bowers v. Hardwick, which criminalized sodomy, denying same sex couples the basic protection for intimate conduct in the privacy of their homes (Bowers v Hardwick, 1986). In 1993, the Congress “thwarted a proposal to extend the spousal-leave provision of the Family and Medical Leave Act to same-sex domestic partners by defining ‘spouse’ as ‘a husband or wife” (Litigating the Defense of Marriage act, 2004, p. 2685). Also, “concurrent with the consideration of DOMA, the Senate debated the Employment Non-Discrimination Act of 1996 (ENDA), which would have prohibited employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation” (Litigating the Defense of Marriage act, 2004, p. 2688). However, ENDA was defeated in the Senate, in September of 1996, the same month DOMA was officially enacted as a federal law (Litigating the Defense of Marriage act, 2004, p. 2686). Accordingly, no same-sex couple could secure a marriage license for nearly eight years after DOMA’s passage (Litigating the Defense of Marriage act, 2004, p. 2687).

The framing of marriage in DOMA and the definition of spouse contradicted United States Supreme Court’s due process jurisprudence on intimate relationships and marriage. The jurisprudence on intimate relationships and marriage “strongly suggest[s] that the freedom to enter into a civil marital relationship with the partner of one’s choice – without reference to gender or sexual orientation – is a fundamental right of all individuals” (Litigating the Defense of Marriage act, 2004, p. 2688). However, DOMA’s definition of marriage as a union between only one man and one woman directly infringed on this liberty. Moreover,

Congress’s accompanying assertion that ‘[s]imply defined, marriage is a relationship within which the community socially approves and encourages sexual intercourse and the birth of children’ is wholly inconsistent with the broad view of marriage specifically, and intimate relationships generally, that supreme court jurisprudence has embraced (Litigating the Defense of Marriage act, 2004, p. 2688).

Since “the freedom to marry has been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men”, any restrictions that directly interfere with the right to marry are generally invalid (Litigating the Defense of Marriage act, 2004, p. 2690). Accordingly, by including a federal definition of marriage in DOMA the Congress claimed for itself authority it most likely did not possess (Russay-Kidd, 1997). DOMA was also against the spirit of the general rule that has governed our experience on marriage, lex celebration, provided by the Full Faith and Credit Clause. If DOMA had never been enacted, the state courts would have had to independently analyze whether or not same-sex marriage qualified as an exception to important public policy (Russay-Kidd, 1997). Instead, DOMA allowed states to refuse recognition of same-sex marriage without such analysis. DOMA thus marked the modern segregation in terms of marriage.

It was only in 2013 that DOMA was challenged in the court, leading to the landmark USSC ruling in United States v. Windsor (2013), which radically changed the legal path with respect to recognition of same-sex marriage. Edith Windsor filed a federal case after the death of her same-sex spouse, claiming federal estate tax exemption, as they were legally married in Ontario, Canada before moving to New York. She challenged the constitutionality of DOMA’s definition of marriage as between man and woman under the Equal Protection clause of the Fifth Amendment. The Court determined Section Three of DOMA was “a deprivation of the equal liberty of persons that is protected by the Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution.” The Court ruled that this section violated basic due process and equal protection principles applicable to the Federal Government and that “the Constitutional guarantee of equality must at the very least, mean that a bare congressional desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot justify disparate treatment of that group” (United States v. Windsor, 2013). The Windsor Court deemed that DOMA’s avowed purpose was to impose a disadvantage, and a separate status to all those who enter into same-sex marriages. Justice Kennedy wrote:

The federal statute is invalid, for no legitimate purpose overcomes the purpose and effect to disparage and to injure those whom the State, by its marriage laws, sought to protect in personhood and dignity. By seeking to displace this protection and treating those persons as living in marriages less respected than others, the federal statute is in violation of the Fifth Amendment (United States v. Windsor, 2013).

The ruling was path breaking and opened the possibility of federal recognition to same-sex marriage as the highest federal court deemed marriage not inclusive of only a man a woman, thus setting a new tone (United States v. Windsor, 2013). Following Windsor, in 2015 the Supreme Court in another landmark case, Obergefell v. Hodges, held that the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same sex couples by both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. Both Windsor and Obergefell thus paved a path to legal recognition of same-sex marriage, in the process also enabling social acceptance of LGBT rights. While much has to be achieved with respect to social acceptance, the courts have opened up possibilities.

Comparing the legal recognition of same-sex and interracial marriage

Obergefell v. Hodges and United States v. Windsor are pivotal to the national conversation on marriage equality and extended the efforts made in Loving v. Virginia, the first national case to bring attention to marriage equality by declaring that bans on interracial marriage were unconstitutional. Obergefell and Windsor not only opened the door to recognition of same sex marriage, but also, through protection of marriage equality as established in Loving, the right to choice and identity as affirmed in Perez v. Sharp (1948) and the right to privacy as acknowledged by the court in McLaughlin and later, in Lawrence V Texas (2003), and showed the historical parallels between interracial and same sex marriage.

Loving is analogous to modern restrictions on same-sex marriage in many ways, as the decision essentially outlined that marriage is a fundamental right (Mezey, 2009). As Susan G. Mezey explains, Loving remains the “most important, most coherent, clearest, most frequently cited case in explaining the constitutional righto marry” (Mezey, 2009, p. 77). The Court in Loving declared:

The freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men …marriage is one of the ‘basic civil rights of man,’ fundamental to our very existence and survival [and that the denial of this fundamental freedom is] so unsupportable on a basis as the racial classifications… and [is] so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Loving’s declaration that the freedom to marry is a basic right to be enjoyed by all citizens of the United States is directly relatable to the restrictions on same-sex marriage. Although the case addressed the Fourteenth Amendment and issues of race, Loving clearly declares marriage as a fundamental right, and hence remains foundational to the discussion of same-sex marriage.

It is alarming and concerning that despite this legal precedent, the rights of same-sex couples were infringed. As noted, although Loving guaranteed a fundamental right to marry, it did not discuss the questions of identity based discrimination. The question of identity, however, had received some recognition in 1948, Perez v. Sharp (1948), a case involving an interracial couple that petitioned the California Supreme Court for a marriage license. The court ruled that marriage is a fundamental right, equivalent to the right to have offspring; legislation infringing on the rights to marry and procreation must be “based upon more than prejudice and must be free from oppressive discrimination to comply with the constitutional requirements of due process and equal protection of the laws” (Perez v. Sharp, 1948). Perez brought to light questions of identity-based marriage restrictions in a way that Loving later failed to do (Lenhardt, 2008). Unlike Loving, Perez focused on the right to marry the person of one’s choice, not just striking down the “white supremacist subtext of the anti-miscegenation laws” (Lenhardt, 2008).

The right to privacy is also central to same-sex marriage debates in the country, along with marriage equality and identity based rights. The Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Lawrence v. Texas, which overruled Bowers v. Hardwick, legitimized the right to privacy for same sex-couples. The petitioners in this case challenged a Texas statute that forbade sodomy. The United States Supreme Court held that the Texas statute prohibiting certain intimate sexual conduct violated the Due Process Clause. The decision and rationale in Lawrence was quite similar to the holding rendered in an interracial case from 1962, McLaughlin v. Florida.

In this case, an interracial couple who lived in the same household were arrested in Florida for adultery and fornication. Section 798.05 of Florida’s statute forbade any opposite sex, unmarried, white and Negro persons to “habitually live in and occupy in the nighttime the same room.” The couple was not able to defend their relationship against the Florida rule because their marriage was deemed invalid due to their racial differences. The trial court convicted the petitioners, however the Florida Supreme Court struck down the statute prohibiting interracial marriage, deeming that it violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Although McLaughlin does not have any iconic impact on the fight for the constitutionality of interracial marriage, it paved the road to recognition of privacy rights by striking down a state law regulating sex outside of marriage.

Following this, Lawrence extended constitutional protection to same-sex intimacy when a couple could not have married under any state law, setting the precedent for consenting same-sex couples to engage in all intimate relations in the privacy of the home. Justice Kennedy’s opinion in Lawrence made it clear that the “relationship between [between same-sex couples is] worthy of both constitutional protection and sociocultural respect” and that the case was not just a fight for sex, but for a relationship worthy of constitutional protection (Dubler, 2006).

Conclusion

The legal recognition of same-sex marriage is undeniably a reflection of social acceptance, and vice versa. This was also noted in the Supreme Court decision on interracial marriage in 1967, where interracial relations were found to be less controversial around the nation. The same argument has been made for same-sex marriage, claiming that, “given the context, a Fourteenth Amendment decision upholding a national right to same-sex marriages would be much bolder than Loving was” (Kersch, 1997). The parallel legal developments are important too, as they demonstrate the framing of identity issues and discrimination and hold potential for future questions on equality. The legal development additionally demonstrates that recognition of civil rights are contingent on social acceptance and mobilization. While Windsor and Obergefell have cleared legal obstacles for LGBTQ rights, social acceptance needs to follow the law so as to ensure equal dignity for all.

References:

Anonymous. (2004). Litigating the Defense of Marriage Act: The Next Battleground for Same-Sex Marriage. Harvard Law Review, 117(8), pp.2684-2707. doi:10.2307/4093411

Dubler, Aricla R. (2006). From McLaughlin v. Florida to Lawrence v. Texas: Sexual Freedom and the Road to Marriage. Columbia Law Review, 106(5), pp. 1165-1187.

Feldmeier, John P. (1995). Federalism and Full Faith and Credit: Must States Recognize Out-of-State Same-Sex Marriages? Publius, 25(4), pp. 107-126.

Kersch, Ken I. (1997). Full Faith and Credit for Same-Sex Marriages? Political Science Quarterly, 112(1), pp. 107-136.

Koppelman, Andres. (2005). Recognition and Enforcement of Same-Sex Marriage. Interstate Recognition of Same-Sex Marriages and Civil Unions: A Handbook for Judges. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 153, pp.2143-2194.

Lenhardt, Robin A. (2008). Beyond Analogy: Perez v. Sharp, Antimiscegenation Law, and the Fight for Same-Sex Marriage. California Law Review, 96(4), pp.839-900.

Mezey, Susan Gluck. (2009). Gay Families and the Courts: The Quest for Equal Rights. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Moran, Rachel F. (2001). Interracial Intimacy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2015). Same-Sex Marriage Laws. Retrieved from: http://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/same-sex-marriage-laws.aspx.

Ruskay-Kidd, Scott. (1997). The Defense of Marriage Act and the Overextension of Congressional Authority. Columbia Law Review, 97(5), pp. 1435-1482.

The Official Site of the Tennessee Government. Miscegenation (n.d). Retrieved from: http://www.tn.gov/tsla/exhibits/blackhistory/pdfs/Miscegenation%20laws.pdf

Wallenstein, Peter. (1999). Law and the Boundaries of Place and Race in Interracial Marriage Interstate Comity, Racial Identity, and Miscegenation Laws in North, South Carolina, and Virginia, 1860s – 1960s. Akron Law Review, 32(3), pp.1-19.

[1] Kristi Intorre is a Law and Society graduate of Ramapo College and is currently studying law at Pace University School of Law.

Thesis Archives

| 2020 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2014 |Copyright ©2024 Ramapo College Of New Jersey. Statements And Policies. Contact Webmaster.