- About Ramapo

- Academics

- Admissions & Aid

- Student Life

- Athletics

- Alumni

- Arts & Community

- Quick Links

- Apply

- Visit

- Give

The International Refugee Regime: A Failing System

(PDF) (DOC) (JPG)December 20, 2014

Nicole Triola [*]

In 1921, the High Commissioner of the League of Nations coined the term refugee and began what would be later known as the international refugee regime (Feller, 2001, p. 584). Today the international refugee regime is the body of law that surrounds international migration based on safety and persecution. The regime outlines the rights, obligations, and responsibilities that sending and receiving states have to asylum-seekers, refugees, as well as other states. The regime was formed as a reactionary measure to combat the consequences of the Balkan Wars, World War I, and many conflicts thereafter. The most important legislative piece of the international refugee regime is the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. This convention defines a refugee as someone who leaves their country of origin due to a real fear of persecution based on their race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion (UN General Assembly, 1951). Refugees are a special category of people that are deserving of protections due to their vulnerable state.

The international refugee regime, and in particular the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, is failing at protecting and providing resources for refugees. This issue is important because the face of modern warfare has changed as the line between soldiers and civilians is blurred and civilian attacks are becoming a war strategy (Feller, 2001, p. 587). Consequently, there have been disproportionately large numbers of refugees created through all types of violent conflicts. The most recent example of a refugee crisis is Syria, with over nine million refugees (“Syrian Refugees”, 2014).

From the beginning, the international refugee regime has developed in patchwork fashion, with attempts to cover issues and concerns that were not originally thought of when founding conventions and declarations were drafted. As a result, there are significant holes in the system. The two major shortcomings that will be discussed are sexual orientation as a missed group in the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, as well as burden-sharing as it relates to the Dublin regime for asylum seekers within the European Union. Sexual orientation as a missed group revolves around the vague wording of the 1951 Convention and the excessive discretion that exists within the asylum application process. Burden-sharing revolves around the overwhelming number of asylum-seekers in certain Member States of the European Union, particularly Greece.

In order to analyze sexual orientation as a missed group and burden-sharing, this paper will utilize personal stories, which allow the reader to get a sense of what is actually happening around the world as a consequence of these difficulties within the regime. The laws and policies surrounding each of the concepts will also be investigated in detail in order to understand the origin of the current problems. The paper will also analyze two landmark cases in order to assess what the legal community has to say about these shortcomings. The real life examples, legislative investigation, and court analysis will give a well-rounded perspective of how the failures to include sexual orientation as a group in the 1951 Convention and to rectify the issue of burden-sharing are leading to massive human rights violations for refugees around the world.

The history of the international refugee regime

The current international refugee regime is riddled with difficulties and shortcomings that negatively affect those the regime is meant to protect. In order to better understand the complexities that exist within the regime it is crucial to understand its history. The regime was produced through a series of reactive measures that have built over time to result in what is known as the international refugee regime. A certain pattern has created the international refugee regime: a conflict arises and an institution is created in order to deal with the conflict and its consequences. None of the institutions so created were meant to sustain an entire international regime.

Conflicts between different state and territorial entities have existed since the beginning of time. Oftentimes such conflicts result in destructive conditions that force people to leave their homes. Today these people are referred to as refugees. While the problem of refugees has always existed, there has not always been a shared international sense of responsibility to provide protection and services for displaced peoples (Feller, 2001, p. 584). It wasn’t until the twentieth century that the refugee dilemma was truly recognized as needing attention and a solution. In 1921, the League of Nations became the first international body to define the term refugee and begin what would be later known as the international refugee regime (Feller, 2001, p. 584).

In the wake of the Russian Revolution and World War I, over one million people left Russian territories for safer destinations. The primary form of aid given to those that left the Russian Empire was charitable donations from numerous public and private organizations (Jaeger, 2001, p. 727-728). The relief effort lacked a central body to coordinate and communicate with counterparts and to effectively raise funds to assist this group. In response to this issue, on February 16th, 1921, the Joint Committee of the International Committee of the Red Cross and the League of Red Cross Societies held a conference that established a High Commissioner to “define the status of refugees, to secure their repatriation or employment outside Russia, and to coordinate measures for their assistance” (Jaeger, 2001, p. 728). Dr. Fridtjof Nansen, the first appointed High Commissioner, defined refugees by their specific country of origin and also created “identity certificates” for the refugees (Feller, 2001, p. 584).

Under Dr. Nansen several institutions were assembled: the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, Office of the High Commissioner of the League of Nations for Refugees, and the Nansen International Office for Refugees, in order to effectively assess and combat the refugee problem at the time (Jaeger, 2001, p. 729). The institutions evolved to include representatives from several countries around Europe, and with their input led to the drafting of the 1933 Convention Relating to the International Status of Refugees. The Convention Relating to the International Status of Refugees “… dealt with administrative measures, refoulement, legal questions, labor conditions, industrial accidents, welfare and relief, education, fiscal regime and exemption from reciprocity, and provided for the “creation of committees for refugees” (Jaeger, 2001, p. 730). It was the first reactive measure taken by the international community and the first supranational convention of its kind created with the goal of assisting those displaced from war and conflict.

The next building block of the international refugee regime was the establishment of the International Refugee Organization (IRO) by the UN General Assembly on December 15th, 1946 (Jaeger, 2001, p. 732). The aftermath of World War II was devastating and the primary concern of the IRO was to resettle the refugees from around the world, as opposed to focusing on rehabilitation or reparation (Gallagher, 1989, p. 579). As the number of refugees continued to grow, it became clear the institution would not complete the resettlement by 1950, which was the year the organization was set to dissolve. In conjunction with various other institutions, the IRO resettled over one million people between 1947 and 1951 (Jaeger, 2001, p. 732). In light of the continued need for the services provided by the IRO, the Commission on Human Rights and the Economic and Social Council requested the Secretary-General to undertake a study to examine the refugee situation and make recommendations for the UN to consider moving forward (Jaeger, 2001, p. 733).

Creation of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and 1951 Convention

The study that resulted, A Study of Statelessness, examined the situation of refugees in several important aspects including expulsion, social security, international travel, education, relief, and many others. In order to present a recommendation on the most effective way to handle stateless persons, the Study concluded that:

“The conferment of a status is not sufficient in itself to regularize the standing of stateless persons and to bring them into the orbit of law; they must also be linked to an independent organ which would to some extent make up for the absence of national protection and render them certain services which the authorities of a country of origin render to their nationals resident abroad.” (Jaeger, 2001, p. 734)

The independent institution the Study referred to was reminiscent of the League of Nations’ High Commission. A final suggestion made in the Study was that the Economic and Social Council “recognize the necessity of providing at an appropriate time permanent international machinery for ensuring the protection of stateless persons” as opposed to institutions that had an expiration date (Jaeger, 2001, p. 735). After taking various proposals into consideration, the UN General Assembly created the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

The primary concern of the UNHCR and 1951 Convention were the remaining million people that were still stateless after fleeing the Nazi regime. Because this institution was created in response to the devastation of World War II, it can also be classified as a reactive measure (Feller, 2001, p. 585). The UNHCR was granted a meager $300,000 budget to assist those that were still in flight, with a three year “temporary authority” to do so (Gallagher, 1989, p. 580). Along with the undersized budget, the Convention was also limited in its application, as it applied only to those persons “affected by the events occurring in Europe (or elsewhere) before 1 January 1951” (Gallagher, 1989, p. 580). Therefore, the protections provided by the Convention were only granted to those that had already been affected, and not to future stateless persons. Still, the Convention “was the first [and indeed remains] the only binding refugee protection instrument of a universal character” (Feller, 2001, p. 585).

The Convention spelled out various rights and protections afforded to refugees, one of the most important being the binding definition of what qualifies a person as a refugee:

“Owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.” (UN General Assembly, 1951)

The definition was significant because it set the standard for identifying a person as a refugee and granted refugees access to the rights and protections in the Convention (assuming they became stateless before January 1st, 1951). Another essential component of the Convention is the article on non-refoulement. Non-refoulement is the principle against forcibly expelling a refugee back to a territory where “his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” (UN General Assembly, 1951). The Convention is made up of forty-six articles that answer questions about refugee rights concerning freedom of movement, identity papers/travel documents, social security, non-discrimination, access to courts, and others.

The Convention strongly reinforced the idea of resettling refugees by promoting the options of assimilation, naturalization of the refugees in the countries that granted them asylum, as well as voluntary repatriation (Gallagher, 1989, p. 581). One could argue that the parameters of the Convention, including the definition of a refugee, date requirement, and policies toward naturalization or repatriation consequently resulted in a quite limited Convention. The reason for the limitations imposed by the 1951 Convention was to keep the number of refugees at a minimum (Gallagher, 1989, p. 581). The UNHCR was already operating on a measly budget that was expected to cover legal protections and the “promotion of durable solutions” (Gallagher, 1989, p. 581). If the UNHCR required supplementary funds beyond the base $300,000 in order to perform their duties, they were obliged to draft “special agreements with governments to “improve the situation of refugees” (Gallagher, 1989, p. 581). However, there was a general understanding that seeking contributions from local governments should not become common practice.

The end of “temporary authority” and introduction of the 1967 Protocol

The next period of time concerning the UNHCR was one of dormancy. While the Cold War produced hundreds of thousands of stateless people in need, the UNHCR remained inactive. The UNHCR was dormant due to the restrictive nature of the Convention and lack of money. The “Cold War refugee problem” was handled by various agencies that did not involve the UN (Gallagher, 1989, p. 582). The preventive funds and definitions immediately became roadblocks to gaining Convention signatories and supporters. In fact, “between 1951 and 1956, the survival of UNHCR was very much in doubt” (Gallagher, 1989, p. 582). However, the agency was granted three million dollars from the Ford Foundation that kept it from completely dissolving.

A turning point in the life of the UNHCR and 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees occurred in 1956, when 200,000 Hungarians fled their country and migrated to Austria and Yugoslavia (Gallagher, 1989, p. 582). This was also the year that the UNHCR’s three year “temporary authority” was due to expire. A 1956 UN General Assembly Resolution granted the UNHCR the authority to lend support and assistance to the fleeing Hungarians (Gallagher, 1989, p. 582). The UNHCR’s activities post-1956 illustrated the “usefulness of having a nonpolitical humanitarian international agency on the scene in situations where significant political interests and sensitivities are at stake” (Gallagher, 1989, p. 582). The success achieved through aiding the Hungarian refugees secured the UNHCR’s survival.

Again in 1958 and 1959 the UNHCR operated under approved assistance in order to give humanitarian aid to Algerian refugees in Morocco and Tunisia, as well as to Chinese refugees in Hong Kong (Gallagher, 1989, p. 582). It was becoming clear that the UNHCR and the 1951 Convention were useful outside their original narrow scope. The early 1960s were not plagued with any massive movements of people, but it became a time for the General Assembly to seriously examine the limitations of the Convention. A Protocol was drafted and approved by the UNHCR’s Executive Committee, and also the General Assembly, to address some of these limitations. The required number of state signatories was promptly reached and in 1967 a Protocol was added to the 1951 Convention (Gallagher, 1989, p. 583). The Protocol authoritatively lifted the time and geographical limitations that existed, and allowed the UNHCR to provide support without cumbersome special regulations from the General Assembly (Gallagher, 1989, p. 583).

The 1960s and 1970s were marked by the process of decolonization in Africa, which violently led to a substantial amount of people fleeing their country of origin (Gallagher, 1989, p. 583). A particular problem that plagued the movements throughout Africa was that people were leaving their own poor countries and traveling into other similarly deprived territories that were already struggling to support their inhabitants. This presented a unique predicament for the UNHCR. In order to cope with supporting those in extremely poor countries that lacked basic resources, the General Assembly again took to drafting special resolutions for the UNHCR to raise money. However, the humanitarian effort in Africa revolved around direct assistance of refugees versus the more legal nature of assistance that was provided throughout Europe (Gallagher, 1989, p. 583). The UN recognized the special circumstances of Africa’s decolonization and together with the Organization of African Unity drafted the 1969 Convention on the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa.

During the late 1970s, the UNHCR dealt with its first burden-sharing situation. The world was witnessing Vietnamese people fleeing their homes in fragile boats, only to be rejected and sent away once they reached the shores of nearby countries (Feller, 2001, p. 586). The solution to this difficulty would only come to fruition if multiple countries could come together with the UNHCR and agree on a plan of action. Consequently, in 1979 the International Conference on Refugees and Displaced Persons in South-East Asia was held in Geneva to discuss the concept of burden-sharing and possible solutions (Feller, 2001, p. 586). The result was the Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA) for Indo-Chinese refugees that entailed a three-way agreement, which included countries offering asylum, the countries of origin, and donor countries (Feller, 2001, p. 586). The UNHCR’s facilitation of this multi-party agreement in response to the crisis in Vietnam once again expanded the scope of the international refugee regime.

Shift to modern day

The 1980s marked the shift of the international refugee regime into its modern day form. The world’s problems and mounting number of refugees began to escalate more quickly than the UNHCR could match or be prepared for. The sheer number of stateless people grew exponentially and there were soon large pockets of refugees located on every continent in the world (Gallagher, 1989, p. 584). The most notable population movement was from Eastern to Western Europe. Many citizens left places like Turkey for economic reasons and became guest workers in Western European countries. When their visa expired, it became common practice for people to plead for asylum in order to stay in Western Europe. Consequently, “the close relationship between their [migrants] economic and political motivations brought into question the refugee status of these migrants” (Gallagher, 1989, p. 593). The UN General Assembly had more asylum-seekers than they could give support to and growing difficulties regarding defining each person’s status.

In Europe, the changes that resulted from the confusion surrounding each person’s status and general overflow of refugees led to the creation of the Dublin system, first established with the adoption of the Dublin Convention in 1990. The Dublin Regulation became part of the international refugee regime in 2003 by expanding the Dublin Convention and making the process for refugees applying for asylum in receiving countries more effective (Gallagher, 1989, p. 593). The Dublin Regulation was further updated in 2013 (Dublin III). A common problem addressed by the Dublin regime was the following: stateless people arrived in receiving countries, applied for asylum, and then moved on to another country and applied for asylum a second time. This created a backlog and slowed down the process of reviewing applications for asylum. In the event that a person does apply for asylum in country A and moves on to country B before having their application reviewed and decided upon in country A, country B can send that stateless person back to country A (European Parliament, 2003).

The number of refugees in need of assistance in the new millennium skyrocketed to an unprecedented 25 million people (Feller, 2001, p. 587). Due to the exponential number of refugees, the focus of the international refugee regime and UNHCR shifted from voluntary repatriation, resettlement, and assimilation to merely attempting to control the influx of people. Soon countries that held refugee camps were experiencing negative consequences: “even in traditionally hospitable asylum countries, there was hostility, violence, physical attack, and rape of refugees” (Feller, 2001, p. 587-588). These unfortunate circumstances led countries to be less likely to be willing to use their time and resources to host refugee camps, especially if the conflicts or circumstances that caused those people to flee weren’t coming to peaceful resolutions in the near future.

In conjunction with the rising number of conflicts around the world, the face of modern conflict was also changing. The happenstance of war, whether internal or external, was yielding more refugees than in the past. One way to explain this change is that human rights violations that were leading to populations fleeing the country were actually becoming a conscious objective of warfare. Therefore, even a smaller conflict yielded a disproportionately high amount of people in need of support and resources (Feller, 2001, p. 587). If we take this change of warfare and maximize it on a global scale, we will end up with a substantial number of refugees and stateless people flooding other countries, which is exactly what happened.

In summary, the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol were not meant to function as the heart of the entire international refugee regime, but rather were forged through a series of responses to conflicts. To this day, there exists a deep disconnect between what the world’s refugees need and what the regime has to offer. The refugee problem has spiraled out of control and our current international refugee regime is not equipped to deal with the situation. In the following chapters, two of the shortcomings of the international refugee regime will be examined in greater detail: sexual orientation as a missed group in the 1951 Convention, and the problem of burden-sharing as a result of the Dublin Regulation.

Sexual orientation does not warrant refugee protection

The international refugee regime is plagued with numerous problems that prevent it from working efficiently and effectively. The following chapters focus on two such difficulties. The first problem analyzed is sexual orientation as a missed group of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. This part of the paper will use a personal story to introduce the complexity of the issue, followed by an examination of relevant policies and implementation of policies. This analysis will show that sexual orientation is not protected as a type of refugee status and is leading to profound human rights violations around the world.

While there are many problems within the international refugee regime, sexual orientation as a missed group is important to investigate in more detail for several reasons. First, sexual orientation as a missed group in the 1951 Convention is a relatively new issue and was thought of in the original drafting of the Convention. As the standards and norms of the international community evolve, challenges arise to force change upon the law to match those evolving standards, and sexual orientation is one such example. Second, sexual orientation is a special issue because of the views on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender tolerance around the world. The recent Olympic Games held in Russia and the highly controversial choice to keep the LGBT athletes out, India’s law against homosexual relationships, and Australia’s failure to pass a same-sex marriage law are just some examples of the homophobia that is still rampant across the world (Chalabi, 2013). This extensive homophobic attitude is also made clear through the practices within the international refugee regime.

The story of Tufan

In his book Embracing the Infidel: Stories of Muslim Migrants on the Journey West, author and scholar Behzad Yaghmaian documents personal stories of migrants in Europe. Through interviews and group conversations, Yaghmaian illustrates the very human aspect of international migration (Yaghmaian, 2005). It is important to review literature that contains personal stories because this emotional human factor can get easily lost when constantly discussing institutions and conventions; after all, the international refugee regime is about protecting people. Throughout the book, the reader is able to understand the different trials and tribulations often facing international migrants. The book highlights various problems within the international migration system and international refugee regime that often lead to despicable human rights violations (Yaghmaian, 2005). Also, individual narratives tell us how the international refugee regime is used in practice versus how it is written in the law.

Yaghmaian documented his meetings with Tufan, a male asylum-seeker from Iran, while they were both in Paris. Tufan was in his mid-twenties and accompanied by a group of other Iranian men that spent the past couple of years attempting to migrate from Greece to France. In the beginning of their conversations Tufan would tell Yaghmaian that he left Iran in order to pursue his dream of becoming a writer, as Iran did not have enough freedom of the press for him to write there safely. However, during one of their meetings Tufan turned to Yaghmaian, “Do you want to tell the real stories of the refugees? … Then you also need to talk about the two forgotten groups. You should talk about gays and lesbians. Many have written about political refugees, but no one is interested in the stories of the gay people” (Yaghmaian, 2005, p. 271).

Tufan then began to describe the lives of several gay men that he had known while still living in Iran. Tufan detailed the behavior of a government entity named the “morality police” responsible for the imprisonment, torture, sexual assault, and death of several openly gay men in Tehran, Iran (Yaghamaian, 2005, p. 272-275). As Tufan continued to retell stories of passed friends, he began to introduce his own life and struggles. Tufan had applied for asylum in France under the political category of the 1951 Convention but was denied due to lack of evidence. Shortly after the denial it was disclosed to Yaghamaian that the stories Tufan knew about the gay community in Iran hit very close to home. The truth about Tufan was that he was a gay man who had been forced into marriage, and that his wife was still waiting for him to return to Iran and was unaware of his homosexuality. Tufan knew that due to the circumstances of his life, his chances of being accepted for asylum based on his sexuality would be entirely up to his interviewer. This burden was insurmountable for Tufan, who sullenly explained, “Sometimes I wish to die. I wish to go to sleep and never wake up.” (Yaghamaian, 2005, p. 282).

Sexual orientation as a missed group

Tufan’s trials and tribulations allow for an unedited look into the system in practice. We can take the life of Tufan and explore sexual orientation as a missed group in the 1951 Convention in order to try to understand how this specific limitation led to the human rights abuses Tufan and his friends suffered. The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol define refugees based on well-founded fear in relation to five categories: race, religion, nationality, or membership in a particular social or political group (UN General Assembly, 1951). It was only in the early 1990s that a public debate began on what protections, if any, the LGBT community was afforded through the 1951 Convention (Wessels, 2011, p. 9). This problem is important because it is contemporary and affects many people like Tufan. However, the lack of data collection makes it very difficult to provide statistics (Jansen & Spijkerboer, 2011, p. 15). Over the past twenty-some years, two major points have emerged: the problems resulting from the lack of clarity of important terms in the 1951 Convention, which led to the overwhelming amount of discretion possessed by decision-makers when reviewing an applicant’s file.

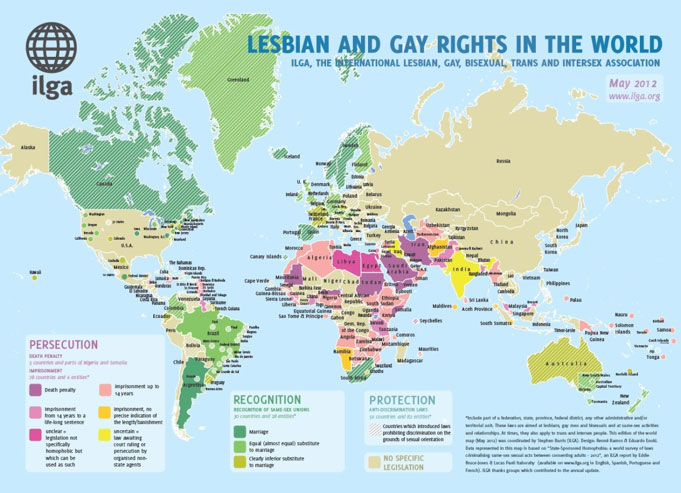

The graph below was published by the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association in 2012 and illustrates the state of LGBT rights around the world. The map uses pink, purple, and yellow to exemplify the number of countries that have laws discriminating against homosexuality. The range of punishments each country holds for homosexuality or homosexual acts ranges from a term of imprisonment all the way to a death sentence (Lesbian and Gay Rights in the World, 2012). An important note to make regarding the map is that the neutral colored countries are labeled as having “no specific legislation,” but this does not mean homosexuality is accepted. There are numerous countries that may not have explicit laws pertaining to the criminalization of homosexuality, but persecution could be a socially accepted practice, which would still give cause to members of the LBGT community to be in fear and flee.

Defining “membership to a particular social group”

The first important piece of identifying sexual orientation as a missed group of the 1951 Convention revolves around how the Convention’s definitions have been interpreted and applied. The 1951 Convention states that those who are “persecuted” and have a “well-founded fear” due to their “membership to a particular social group” are considered refugees and deserve the protections and rights outlined throughout the Convention (UN General Assembly, 1951). However, what exactly does “membership to a particular social group” mean? Unfortunately, this mention of membership in the Convention is the least clear of the five listed, so it has been left up to interpretation. In 2008, the UNHCR published the Guidance Note on Refugee Claims Relating to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, providing some clarity on the matter (Wessels, 2011, p. 5). The Guidance Note defines “membership of a particular social group” as:

“A particular social group is a group of persons who share a common characteristic other than their risk of being persecuted, or who are perceived as a group by society. The characteristic will often be one which is innate, unchangeable, or which is otherwise fundamental to identity, conscience, or the exercise of one’s human rights.” (UNHCR, 2008)

This definition was intended to fuse together two dominant views: a “characteristics” approach and a “social perception” approach on membership through case law (Wessels, 2001, p. 11). While this proposed definition by the UNHCR offers more substance than the category listed in the 1951 Convention, it remains vague. The definition does not present an explicit consensus on how to define “membership to a particular social group” and clearly makes no admission to the LGBT community in particular. A major criticism that suggests this definition is lacking is the fact that all members of the LGBT community do not share one common characteristic. Even if “same-sex attraction” could be used to describe people who identify as lesbian or gay, it would still leave out transgender, bisexual, and intersex peoples (Wessels, 2011, p. 13).

Unclear terms and the problem of discretion

Furthermore, defining “persecution” and “well-founded fear,” which are essential elements to qualifying a person as a refugee, are equally puzzling. The 1951 Convention does not offer clarification and there is no universally accepted designation of the terms (Wessels, 2011, p. 15). Because of this lack of clarity or specificity, when an asylum-seeker lodges an application for refugee status based on LGBT status, it is entirely up to the decision-maker reviewing their file to accept their case. This results in the decision-maker possessing an unfair amount of discretion over the fate of the applicant and leaves the opportunity for personal biases to interfere with and influence the ultimate outcome.

The UNHCR’s Guidance Note refers to persecution as involving “serious human rights violations, including a threat to life or freedom, as well as other kinds of serious harm, as assessed in light of the opinions, feelings, and psychological make-up of the applicant” (UNHCR, 2008). The difficulties that result from this definition are assessing what kind of decision-maker could be qualified to evaluate those deeply personal attributes of a person, as well as how to judge whether someone is in jeopardy of persecution. In many countries that legally or socially condemn homosexuality, secrecy is a necessary part of life for someone belonging to the LGBT community. How can the UNHCR guarantee that every decision-maker will be qualified to psychologically assess an applicant? Many applicants have spent their entire life lying to those around them.

Secondly, in order to evaluate whether an applicant is in jeopardy, decision-makers are charged with assessing if the fear is “well-founded.” The concept of “well-founded” can be expanded to include a “reasonable degree of likelihood” or “real risk” that the applicant will face persecution if they return to their country of origin (Wessels, 2011, p. 15). However, how are decision-makers supposed to evaluate the risk of persecution? If a country has explicit laws discriminating against homosexuality, the risk of persecution can easily be judged as real and imminent. However, oftentimes a country will not have specific legislation against homosexuality, but more general laws against acts “undermining public morality” that are functionally equivalent (Wessels, 2011, p. 17). These discriminatory laws are not always easy to identify and this creates an undue burden on the applicants to prove their circumstances.

It is therefore crucial to the rights of LGBT individuals that vague definitions are clarified and the abundance of discretion afforded to decision-makers is remedied: “Such clear words reduce the discretion of decision-makers in sexual orientation cases to use the interpretation of the particular social group to exclude gay refugees from protection, and provide lower-level decision-makers with legal guidance on the matter” (Wessels, 2011, p. 14). Therefore, changes need to be made to ensure the LGBT community has access to refugee status. One possible way for these changes to come about would be through the international court system.

Sexual orientation, discretion, and the courts

Sexual orientation as a missed group has presented various problems for the international refugee regime. One of the biggest problems discussed has been discretion. When an asylum-seeker makes an application for refugee status their case is heard and ruled on by a decision-maker. The decision-maker is capable of using unfair amounts of discretion when judging if an applicant should be granted refugee status (Wessels, 2011, p. 15). One way to gather information on the negative consequences of too much discretion is through understanding personal stories. The story of Tufan illustrated the fear that applicants experience at the thought of having the decision left up to their interviewer, especially since their sexual orientation is such a controversial aspect of their lives (Yaghamaian, 2005, p. 282).

Court cases also illustrate the problem of discretion in cases involving sexual orientation, specifically through the “reasonable tolerability” test that requires LGBT applicants show prudence in their private lives, and through the unfair amount of discretion the interviewer has when reviewing an application. By looking at various European court decisions, a clear norm emerges. Expecting an asylum-seeker to hide their sexual orientation in their home country to avoid persecution is routine and regularly grounds for denying an application for asylum (Jansen & Spijkerboer, 2011, p. 34). The landmark decision made by the United Kingdom Supreme Court in HJ (Iran) & HT (Cameroon) v. Secretary of State for the Home Department (2010) UKSC 31 illustrates the fundamental problem of discretion in the refugee system.

HJ (Iran) & HT (Cameroon) v. Secretary of State for the Home Department (2010) UHSC 31 combines two separate asylum claims from 2001 and 2007. In 2001 an Iranian man, HJ, fled his home country for the United Kingdom and in 2007 a man from Cameroon, HT, also applied for asylum in the UK. Both of these men were openly gay and applied for asylum based on their claims that they had “… a well-founded fear that they would be persecuted if they were to be returned to their home countries” based on their homosexuality (HJ & HT v. SSHD, 2010, p.3). In both Iran and Cameroon practicing homosexuality is a criminal offense that could be punished by imprisonment, or in the case of Iran, execution. The applicant from Cameroon, HJ, had also cited an assault he suffered due to this homosexuality in his application for asylum (European Database of Asylum Law, HJ & HT V. SSHD). After review, both of the applications for asylum were denied.

Following the denial, HT and HJ appealed the decision and the Court of Appeals subsequently rejected their appeals. During this process, the Court learned that if HT and HJ were returned to their countries of origin, both would hide their sexual orientation (European Database of Asylum Law, HJ & HT V. SSHD). The Court used the fact that the men would hide their sexuality as a basis for denying their applications for asylum. In the case of applicant HT the Court proclaimed that if he hid his sexuality he would not come to the attention of the authorities, and would thus be safe from persecution. In the case of applicant HJ the Court cited that he could relocate to another part of Cameroon where no one would know about his homosexuality and therefore he would be unlikely to suffer another attack (European Database of Asylum Law, HJ & HT V. SSHD). The Court cited the “reasonable tolerability” test to support the decision.

A common benchmark for an LGBT person applying for asylum is the secrecy they operate under in their home country. An applicant may hide their sexual orientation due to the reception, rejection, and even persecution they would face from family, friends, co-workers, and the law. “LGBT people who leave their country in order to seek refuge and apply for international protection elsewhere, are often rejected with the reasoning that they have nothing to fear in their country of origin as long as they remain discreet” (Jansen & Spijkerboer, 2011, p. 33). This requirement of being discreet is what has become known as the “reasonable tolerability” test. While reviewing an application a decision-maker would ask themselves, would it be reasonably tolerable for this applicant to hide their sexuality and live in their country of origin discreetly? By living quietly and practicing prudence when it comes to their sexuality the applicant could avoid persecution and thus avoid having to relocate to another country.

The decision in the United Kingdom case concerning applicants HT and HJ is not an isolated one. Courts in Belgium, Norway, Switzerland, Finland, and Germany have all cited the “reasonable tolerability” test or something comparable to it in order to deny applicants refugee status (Jansen & Spijkerboer, 2011, p. 34). A judgment in Belgium stated that

“In Iranian society there is a great difference between public space and private sphere. In practice, homosexuality among men is widespread and accepted…as long as the relationship is kept private … The general “de facto-tolerance” means that, as long as homosexuals live their sexuality in private, it is not very likely that the Iranian authorities will show interest in the person involved … as long as they play it by the rules, homosexual men can interact … without attracting attention” (Jansen & Spijkerboer ,2011, p. 34).

Through case law the “reasonable tolerability” test has become normal practice in reviewing asylum applications connected to homosexuality. This method combines the aforementioned two forms of extreme discretion: discretion on the part of the applicant to hide their sexual orientation and discretion on the part of the interviewer when deciding if the applicant could tolerate living with their sexual orientation in secrecy.

After the appeal in HJ (Iran) & HT (Cameroon) v. Secretary of State for the Home Department (2010) UKSC 31 was denied, the asylum-seekers took the case to the Supreme Court in the United Kingdom. The Supreme Court decided that the “reasonable tolerability” test and those like it were not acceptable standards for judging asylum applications because they violated basic human rights. The Supreme Court ruled that “to compel a homosexual person to pretend that their sexuality does not exist, or that the behavior by which it manifests itself can be suppressed, is to deny the fundamental right to be who he or she is” (HJ & HT v. SSHD, 2010). Furthermore, the Court stated that “persecution does not cease to be persecution if the person persecuted can eliminate the harm by avoiding action” (HJ & HT v. SSHD, 2010, p.3). To deny the applicants refugee status and send them back to their home countries would be in violation of the article on non-refoulement found in the 1951 Convention (UN General Assembly, 1951).

Through the ruling in HJ (Iran) & HT (Cameroon) v. Secretary of State for the Home Department (2010) UKSC 31 the Court has made it clear that the amount of discretion an interviewer has during the asylum process is a problem that has led to the overstepping of boundaries and thus violations of human rights of the applicants. An unknown number of asylum-seekers have already been turned away due to the “reasonable tolerability” test or something analogous to it. While important, this one Supreme Court decision does not change the norm around the world. The widespread homophobic beliefs held around the world are a major barrier to change. The decision is a step in the right direction but until fundamental changes occur in the international refugee regime that clearly indicate that sexual orientation is a possible gateway to asylum, and the amount of discretion held by an interviewer is greatly reduced, human rights violations will continue to occur to many people deserving of protection.

The creation of an undue and overwhelming burden

The second major shortcoming of the international refugee regime discussed is burden-sharing. Burden-sharing pertains to the disadvantages certain Member States of the European Union have when it comes to handling asylum cases. Burden-sharing, like sexual orientation as a missed group, is a particularly important issue to study. The issue of burden-sharing raises critical questions about the intent behind the Dublin system. Are the human rights violations we are seeing as a result of failed burden-sharing the unintended consequences of the Dublin legislation or did legislative intent exist to burden certain Member States?

The story of Purya

The most forceful way to analyze how the international refugee regime has been affected by the downfalls of the Dublin system is through personal stories and experiences. Earlier the story of Tufan showcased how sexual orientation as a missed group is a fundamental limitation of the 1951 Convention. The story of Purya will demonstrate the negative effects that the Dublin Regulation has on the international refugee regime. Greece is known as an internal gatekeeper to the European Union (Yaghmaian, 2005, p. 220). Therefore, Greece is where an overwhelming amount of asylum-seekers end up just because of its location on the border of the European Union. The Dublin Regulation imposes an undue burden on Greece in the international refugee regime. Greece has become responsible for an absurd number of asylum-seekers, and has been unable to handle them.

Purya was originally a street vendor from Iran before he became a refugee in search of safety in the European Union. Oftentimes refugees choose to use a human smuggler to get them into the European Union. Purya and a small group of asylum-seekers he traveled with employed a human smuggler to get them across the border of Bulgaria into Greece, where they would walk to Athens and apply for asylum (Yaghamaian, 2005, p. 180). However, as so often happens, their journey did not go as planned. After walking into Greece the group was picked up by police: “Purya had thought that the police were taking him to Athens, where he would register for asylum … to his surprise, he found out that the car was going in the opposite direction. The police drove the migrants back to where they had entered the country” (Yaghamaian, 2005, p. 181-182). Purya and the group he traveled with were expelled from the European Union without being given the opportunity to apply for asylum.

This expulsion from Greece violated Articles 16, 26, 31, and 32 of the 1951 Convention. These articles cite the states’ responsibility to provide access to courts, freedom of movement, freedom from penalties for being in the country illegally, and from expulsion (UN General Assembly, 1951). Greece, as a signatory to the Convention and as a Member State of the European Union, has an obligation to fulfill the responsibilities cited in the 1951 Convention. After arriving back in Bulgaria the group was immediately taken to a detention center and kept in disgusting conditions for two weeks. This small glimpse into the story of Purya and his journey to apply for asylum shows the unacceptable conditions befalling many refugees. His journey should not be an example of how the international refugee regime functions. The state of the regime is in dire need of reworking and until that time refugees will continue to suffer the consequences of a system plagued by limitations and infectiveness.

Issues raised by the Dublin system

The story of Purya demonstrates the limitations of the Dublin Regulation. In an effort to make the international refugee regime more effective, the European Union began a series of harmonization policies in the 1990s. The Dublin Convention was introduced into international law in 1990 with the goal of making the asylum process more efficient. In accordance with the Dublin Convention an asylum-seeker could only have their application reviewed in the first Member State of the European Union that they entered (Bacic, 2012, p. 46). Next, the Amsterdam Treaty of 1999 outlined tenets that every Member State had to put into effect within five years of the treaty coming into law (Bacic, 2012, p. 46-47). The regulations were to ensure each Member State was in compliance with the minimum standards of asylum as set forth by the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and 1967 Protocol.

Shortly after the Amsterdam Treaty, the Common European Asylum Policy (CEAP) was prepared with the goal of creating a universal asylum procedure between all European Union Member States with consistent rules (Bacic, 2012, p. 48). In 2003, the Dublin II Regulation was passed to expand the Dublin Convention (European Parliament, 2003). The Dublin Regulation further “established the criteria for determining which Member State is responsible for examining a lodged asylum application” (Bacic, 2012, p. 58). The most recent update to the Dublin Regulation, aiming to correct some of the problems raised by Dublin II, came into force in July 2013.

In accordance with the Dublin Regulation, a refugee must make an application for asylum in the first European Union Member State that they enter. “If an asylum-seeker goes to another Member State and also lodges an application for asylum there, he shall be taken back to the Member State responsible. Asylum-seekers … do not have the right to move and reside freely … other than in the territory of the state responsible for their protection” (Bacic, 2012, p. 59). The original logic behind this regulation was to avoid a backlog created by multiple applications (Bacic, 2012, p. 58). However, this regulation has hindered the effectiveness of the application process for asylum, as the geographic location of a Member State is the sole determinant of the number of entries they will receive. Based on location alone, all of the countries located in the eastern and southern parts of the European Union receive the highest amounts of incoming refugees and thus become responsible for filing and reviewing all of their applications (Bacic, 2012, p. 60). The financial liability has become overwhelming and the resources necessary to handle large quantities of asylum-seekers are non-existent. The logical answer to this over-burdening of a Member State would be to transfer applicants to surrounding territories, but the Dublin Regulation prevents that process from happening. Furthermore, if an asylum-seeker moves from their point of entry state for any number of reasons and is caught, s/he will be shipped back, and any existing connections to the second Member State are disregarded (Bacic, 2012, p. 61).

The overwhelming burdens that are placed on states that reside on the periphery of the European Union are best illustrated through numbers: “In some Member States, more than 50% of asylum applications result in success, while in others the percentage is even lower than 1%” (Bacic, 2012, p. 60). Statistics show that Greece has over a 99% rejection rate, which is higher than any other Member State (Greek Council for Refugees, 2013). The Dublin Regulation also introduced a “sovereignty clause,” which allows a Member State to disregard their responsibility to transfer an applicant back to their point of entry state if they are aware the first state is unable to cope with the applicant’s file (Bacic, 2012, p. 58). If the Dublin Regulation were successful in making the asylum process more straightforward, there would be no need for a sovereignty-clause that contradicts the directive it is built into.

The realities of the Dublin system are not without consequence: “The Dublin Regulation, in combination with the other legislative acts of the Union, brings into question the compliance of the European asylum system with international human rights guarantees” (Bacic, 2012, p. 65). A fundamental problem with the Dublin Regulation is that it was drafted on top of the assumption that the harmonization policies of the 1990s were successful. However, statistics show that in “2012 just under one third (31%) of EU first instance asylum decisions resulted in positive outcomes … the share was considerably lower (19%) for final decisions [based on appeal or review]” (Eurostat, 2013). Also, in a country like Greece that functions as an internal gate-keeper for the European Union, acceptance rates are as low as 0.1% (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). These statistics demonstrate that the overburdened states have a much smaller acceptance rate, and the playing field is simply not equal. Not only has operating under the false assumption of harmonization led to overburdening some Member States, but it has also led to the disintegration of human rights guarantees.

The first type of human rights violation has been the increased use of detention centers. These detention centers began as avenues of last resort but have quickly become the first stop for applicants awaiting transfer. These centers are oftentimes not up to international law standards and have earned the reputation for treating asylum-seekers like unlawful prisoners instead of refugees seeking assistance (Bacic, 2012, p. 65). For example, “The Committee for the Prevention of Torture of the Council of Europe [CPT] noted in the report on their last visit in 2011 that the design of detention centers in Greece do not respect the CPT standards and have not respected them at least since 1997” (Detention Conditions, 2013). Article 31 of the 1951 Refugee Convention provides that “the Contracting States shall not impose penalties, on account of their [refugees] illegal entry or presence” (UN General Assembly, 1951). The use of detention centers and their prison-like conditions is in clear violation of this article. If the conditions of the detention centers in Greece have been in violation of numerous laws for over ten years, why has no effort been made to change them?

The next type of human rights violation is the varied reception conditions in each Member State. The 1951 Convention outlines the basic responsibilities of receiving states towards incoming refugees in Articles 16, 21, and 24. They include access to courts, housing, and social security (UN General Assembly, 1951). However, some member states, such as Greece, are unable to cope with the number of applicants in their country, so these guarantees are not being fulfilled (Bacic, 2012, p. 65). Asylum-seekers are being cheated out of the resources they are afforded through the 1951 Convention and their rights are being violated. Oftentimes asylum-seekers are left homeless on the streets of cities and given no resources for obtaining basic housing, food, or medical care (M.S.S v. Belgium and Greece, 2011).

These key shortcomings of the Dublin system, and in particular burden-sharing, are clearly revealed in landmark European decisions on refugees, primarily M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece (2011), examined next. It is important to note that this is not an isolated case, but just one example of a refugee suffering due to the failing international refugee regime. It is helpful to analyze how the courts have begun to deal with the issue of burden-sharing and how they critique the overall refugee regime.

M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece (2011)

The problem of burden-sharing is very different from the problem of sexual orientation as a missed group in the 1951 Convention. Burden-sharing became a major difficulty due to the parameters of asylum established by the Dublin system, while sexual orientation as a missed group was simply not considered during the drafting of the 1951 Convention. However, both shortcomings result in human rights violations.

In 2008, an Afghan national left Kabul and entered the European Union through Greece after traveling through Iran and Turkey. The applicant arrived in Greece and continued to travel until he arrived in Belgium in 2009 where he immediately applied for asylum (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). However, Belgian authorities submitted a request for the applicant to be transferred back to Greece, because under the Dublin Regulation applications for asylum must be submitted in the first European Union Member State an asylum-seeker enters. After the request for transfer was made, the UNHCR offered a letter to the Belgian Minister for Migration and Asylum Policy expressing their condemnation of the decision to invoke the Dublin Regulation. The UNHCR cited the highly criticized reception conditions in Greece and the overwhelming number of asylum applications Greece had as reasons for Belgium to review the application (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011).

Despite the plea from the UNHCR to cancel the transfer request and Greece remaining unresponsive to the request within the two-month period provided for by the Dublin Regulation, Belgian authorities moved to follow through with the removal. The applicant lodged an appeal to the Alien Appeals Board and claimed he would not only be detained upon arrival in Greece in horrible conditions, but also not receive the proper attention regarding his asylum application and would ultimately be sent back to Afghanistan and put in danger (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). The appeal was denied and the applicant was put on a plane to Greece. Upon arrival in Athens the applicant was placed in a detention center where he was locked up in a small space with twenty other detainees, had restricted access to toilets, was not allowed out into the open air, was given very little to eat and had to sleep on dirty mattresses or on the bare floor (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). After a few days he was released with no money, resources, or a place to go.

Due to these desperate conditions, the applicant attempted to leave Greece but was intercepted and arrested. The applicant was returned to the detention center for a second time and cited that this time he was beaten by the police (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). After his release the applicant continued to live on the streets and survived by taking donations from a local church. No social services or housing were ever offered to him by the Greek authorities. After this experience the applicant lodged a claim and argued that Articles 2, 3, and 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights were violated (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). These articles refer to the applicant’s right to life, right against inhuman or degrading treatment, and right to an effective remedy (Council of Europe, 1950).

The European Court of Human Rights ruled that Articles 3 and 13 were violated and awarded the applicant compensation. In regards to the Greek detention centers, the Court acknowledged the burden that Greece faced, but ruled that “the situation could not absolve Greece of its obligations under Article 3” (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). The conditions inside the prison and the allegation of bodily harm were coupled with various reports by international bodies and non-governmental organizations such as the UNHCR and the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture that confirmed that the immediate placement of asylum-seekers in detention centers is normal practice in Greece. These two forms of evidence were sufficient to rule the detention, albeit short, violated the applicant’s right against cruel or inhuman treatment.

The Court also ruled that Article 3 was violated based on the living conditions the applicant had to suffer through after applying for asylum. The applicant “spent months living in extreme poverty, unable to cater for his most basic needs- food, hygiene, and a place to live- while in fear of being attacked and robbed” (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). While Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights does not explicitly oblige Member States to provide financial assistance to asylum-seekers, the Court found this situation particularly serious. The Court stated that the Greek authorities had to have known the applicant was homeless, especially considering that there are fewer than 1,000 placements available in reception centers to accommodate tens of thousands of asylum-seekers (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). Due to these findings on Article 3, the Court did not examine the claims based on Article 2 of the Convention.

Next, the Court examined if Greece violated Article 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights that guarantee an effective remedy for a violation of a right. The Court found that while guarantees in Greek law for the protection against arbitrary removal of an asylum-seeker existed, they were not being put into practice. The Court found numerous faults within Greece’s asylum procedure, such as: “insufficient information about the procedures to be followed, the lack of a reliable system of communication between authorities and asylum-seekers, the lack of training of the staff responsible for conducting interviews with them, a shortage of interpreters and a lack of legal aid effectively depriving asylum-seekers of legal counsel” (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). Furthermore, while the Greek authorities had an appeal process in place, the Court found the average duration of an appeal was more than five years, and thus did not constitute an effective remedy (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011).

The Court also examined the possible violations of Articles 3 and 13 committed by Belgium. The Court condemned the decision of the Belgian authorities to expose the applicant to the asylum process in Greece despite the letter Belgium received from the UNHCR and the unanswered request to Greek authorities. The Court also ruled that by transferring the applicant to Greece, the Belgian authorities “knowingly exposed him to detention and living conditions that amounted to degrading treatment,” in violation of Article 3 (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, 2011). The Court also found that the appeals process in Belgium did not meet the requirements of the Convention. The outcome of the case was the immediate review of the applicant’s asylum request by Greece, as well as a combined total of 37,975 Euros from Greece and Belgium.

The Dublin Regulation, the story of Purya, and the case of M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece show that the asylum procedure in Greece is not working and that there is no possible way for Greece to have a functional or effective asylum process. The overwhelming majority of asylum applications are denied, there are little to no social services provided, applicants very often end up serving time in foul detention centers, and their human rights are violated in the process. To fix it, the Dublin system needs to be reformed, reception services in Greece improved, and Greece needs to modify its detention centers to comply with international standards. The goal of keeping the number of refugees accepted into the European Union as small as possible needs to be reevaluated. If Greece continues to stand as the bearer of the burden for the majority of asylum applications, then human rights violations will continue to occur and thousands more stateless people that are deserving of asylum status will be denied.

Conclusion

The international refugee regime was founded through a series of reactionary responses to violent conflicts around the world that together created the patchwork system that is in place today. The way in which this system was created explains many of its limitations. One of the most fundamental issues of the regime is that the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees was not originally drafted to bear the weight of the entire international regime. The drafters of the convention were dealing with the consequences of World War II and using retrospection to create a body of international law to deal with the specific challenges facing the international community at that time. In order to build a successful international refugee regime, the gaps created by this backward-looking convention need to be filled in and new legislation needs to be passed.

One of the limitations of the 1951 Refugee Convention is sexual orientation as a missed group. The drafters of the Convention were not concerned with LGBT refugees, as the issue was not acknowledged at the time the Convention was fashioned. In the twenty-first century, LGBT tolerance is a spotlight topic throughout the international community. Currently the international refugee regime is attempting to create guidelines on sexual orientation as a group deserving of protection using the five categories listed in the 1951 Convention, but this is not working. Other institutions within the United Nations have published instructions and suggested interpretations of the terms that dictate sexual orientation as a group warranting refugee status.

Yet there remain two major problems: unclear terms and overwhelming discretion possessed by those who make the decisions on asylum applications. The lack of clarity of important terms and definitions has directly led to decision-makers having an unfair amount of control over the lives of those that are seeking refugee status due to their sexual orientation. This has been illustrated through the story of Tufan as well as the case of HJ (Iran) & HT (Cameroon) v. Secretary for the Home Department (2010) UKSC 31.

The second major limitation of the international refugee regime discussed is the lack of burden-sharing between Member States of the European Union created by the Dublin Regulation. The story of Purya, statistics on reception and detention conditions in Greece, and M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece (2011) show that burden-sharing is necessary for an effective refugee regime. Greece is the most overwhelmed Member State due to its geographical location. Greece has employed coping techniques in violation of international laws and standards for over ten years. The hundreds of thousands of asylum-seekers that pour into Greece every year suffer the consequences of these coping techniques.

The burden Greece bears is too overwhelming to rectify with simple measures, yet there has been no effort by the European Union or international community to force change. The intent behind the initial Dublin Convention and Dublin Regulation was to overburden the Member States on the periphery of the European Union and ultimately limit the amount of refugees accepted into the EU. But the international refugee regime should be a system that is first and foremost concerned with protecting the rights and providing resources for those people around the world that are faced with life-threatening persecution. New laws, declarations, and conventions must be drafted that are not reactionary but are forward-looking. The purpose of new legislation must be to sustain an international refugee regime, and the system needs to be tailored to the cause. Change cannot be suggested, change must be demanded.

References:

Bacic, Nika. (2012). Asylum Policy in Europe: The Competences of the European Union and Inefficiency of the Dublin System. Croatian Yearbook of European Law and Policy, 8, 41-76. Retrieved from: http://www.cyelp.com/index.php/cyelp/article/view/149

Chalabi, Mona. (2013, December 12). State-Sponsored Homophobia: Mapping Gay Rights Internationally. The Guardian. Retrieved from: http://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2013/oct/15/state-sponsored-homophobia-gay-rights

Council of Europe. European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, as amended by Protocols Nos. 11 and 14 (4 November 1950, ETS 5). Retrieved from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3b04.html

Eurostat. (2013, October). Asylum Statistics. Retrieved from: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Asylum_statistics

Feller, Erica. (2001). International Refugee Protection 50 Years On: The Protection Challenges of the Past, Present, and Future. International Review of the Red Cross, 83(843), pp. 581-606. Retrieved from: http://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/581-606_feller.pdf

Gallagher, Dennis. (1989). The Evolution of the International Refugee System. International Migration Review, 23(3), pp.579-598. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2546429

Greek Council for Refugees. (2013). Statistics: Greece. Retrieved from: http://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/greece/statistics

ILGA (2012). Lesbian and Gay Rights in the World [Web Graphic]. Retrieved from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/03/26/whatever-the-supreme-court-decides-these-nine-charts-show-gay-marriage-is-winning/

Jaeger, Gilbert. (2001). On the History of the International Protection of Refugees. International Review of the Red Cross, 83(843), pp.727-737. Retrieved from: http://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/727_738_jaeger.pdf

Jansen , Sabine and Thomas Spijkerboer. (2011). Fleeing Homophobia: Asylum Claims Related to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Europe. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Retrieved from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4ebba7852.html

HJ (Iran) & HT (Cameroon) v. Secretary of State for the Home Department. [2010] UKSC 31 M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, Application no. 30696/09, Council of Europe: European Court of Human Rights, 21 January 2011. Retrieved from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4d39bc7f2.html

Syrian Refugees. (2014, February). Syrian Refugees. Retrieved from: http://syrianrefugees.eu/

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Dublin Regulation 2003. Official Journal of the European Union, Vol. 29. Retrieved from: http://easo.europa.eu/wp- content/uploads/Reg-604-2013-Dublin.pdf

UN General Assembly, Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 28 July 1951. United Nations Treaty Series, Vol. 189, p. 137. Retrieved from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3be01b964.html

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2008). Guidance Note on Refugee Claims Relating to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. Retrieved from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/48abd5660.html

Wessels, Janna. (2011). Sexual Orientation in Refugee Status Determination. Refugee Studies Centre, 73, pp.1-58. Retrieved from: http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4ebb93182.pdf

Yaghmaian, Behzad. (2005). Embracing the Infidel: Stories of Muslim Migrants on the Journey West. New York, NY: Random House, Inc.

[*] Nicole is a 2014 graduate of the Law and Society program at Ramapo College of NJ. She is currently pursuing her Juris Doctor degree at Case Western Reserve School of Law.

Thesis Archives

| 2020 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2014 |Copyright ©2024 Ramapo College Of New Jersey. Statements And Policies. Contact Webmaster.